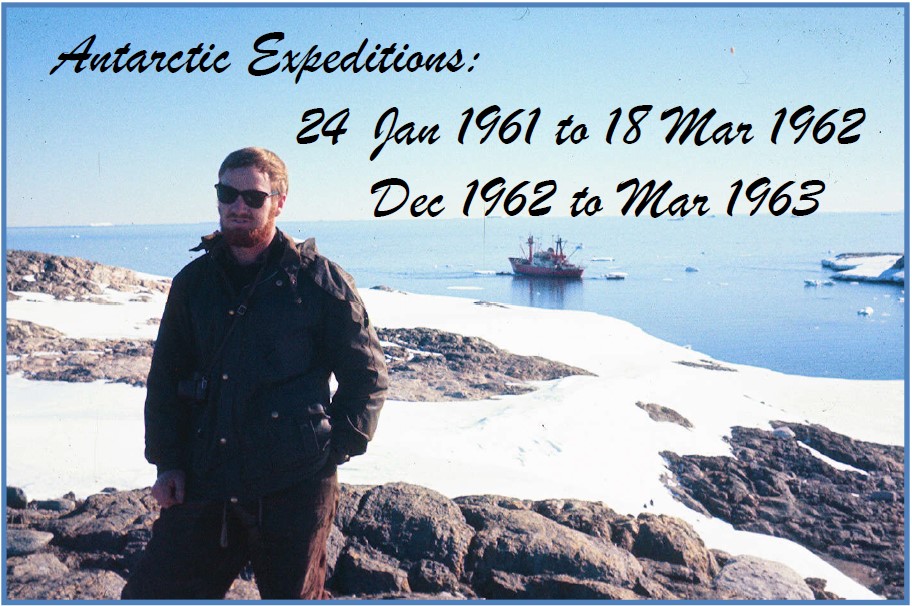

Antarctic Expeditions:

24 Jan 1961 to 18 Mar 1962

Dec 1962 to Mar 1963

Introduction

Soon after graduating at the end of 1959 with an honours degree in physics from the University Western Australia (UWA) I obtained my first full-time job with the Antarctic Division, a unit within the Federal Government Department of External Affairs. This happened as the result of a chance meeting in Melbourne with a friend from St Georges College.

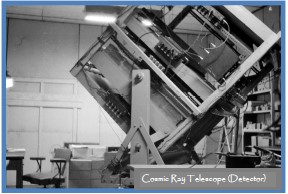

In December 1959 when I commenced a “vacation” job with the Bureau of Mineral Resources in Melbourne, I met Rod Hollingsworth, the friend referred to above. Rod, a Geophysicist, was preparing for the next expedition to Mawson commencing December 1960. Rod had already spent a year at the Australian sub-Antarctic base at Macquarie Island. He was living in an apartment in Kew (Melbourne) with a few guys, one of whom was Neil Houston whom my two brothers knew from their university days. It wasn’t long before I also became enthusiastic about visiting the Antarctic and applied for the position of Cosmic Ray Physicist based at Mawson. My application was successful and I moved interstate to work in the Physics Department of the University of Tasmania which managed Cosmic Ray research. My job in the Antarctic was to monitor the “flux” of Cosmic Rays hitting the south polar region of the earth from three directions – vertically, and from the east and west. To do this, we had a total of three cosmic ray detectors “telescopes”, two of them attached to ex-anti-aircraft gun mountings that swung in opposite directions every hour, 24 hours per day.

Each telescope contained three trays of detectors within a cubic structure. A particle passing through each of the three trays within a very short defined interval was recorded as a single hit. The third telescope was non-directional, designed to detect neutrons from all directions. The data from these telescopes was printed out continuously for later analysis. Station-wide power failures, although not common, occurred often enough to require the telescopes to be re-directed to maintain the sequence of recording east-west-east-west. After just one too many power failures, I became exasperated and inserted additional logic into the controlling circuitry to ensure each telescope faced the correct direction when the power returned. I mentioned this modification to the scientist taking over from me but overwhelmed by the avalanche of instructions during the “changeover” he forgot and it took him some time to finally work out what was happening with the telescopes after a “power failure and recovery” event.

Cosmic Ray Telescope (Detector)

Ian – Field Trip – Tasmania

Every day at Mawson, I had to copy that data manually and have it sent back to the university via our radio operators who transmitted most information using Morse code. I mentioned “manually”, because we didn’t have computers in those days! Nowadays, the data is recorded and transmitted automatically to the university via the internet. The most common analysis was to correlate cosmic ray telescope data with measurements of solar activity which were carried out by the university. The correlation calculations were carried out manually on noisy mechanical calculators that looked like typewriters.

During the change-over period soon after I arrived, I managed to convince our helicopter pilot to take me on one of his flights in the Antarctic Division’s Bell helicopter with a cockpit that resembled a goldfish bowl so that both pilot and passenger had an almost unobstructed view of the landscape in front and below. He obliged with a mind-numbing, high-speed, low level flight over the ice plateau behind the base, flying a couple of metres above the ice plateau towards the coast where the plateau finished with sheer 100 metre cliffs plunging into the sea. It was nothing short of exhilarating, especially when the helicopter flew over the cliff and the ice plateau suddenly vanished, being replaced by a black-coloured sea 100 metres below.

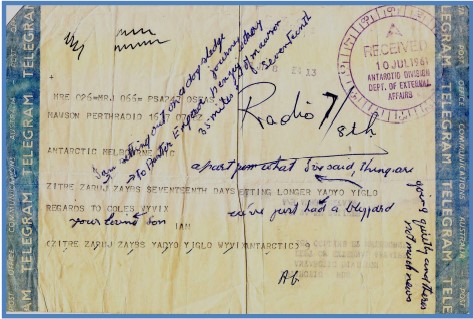

Expedition members were only able to contact their friends and relations in Australia via telegram and to save radio time, code words were used to replace normal phrases like “I am well”. An example of such a telegram I sent home and fortunately preserved by mum, is shown above. Examination of the telegram reveals code words such as ZITOG, ZARUG, ZAYBS and many others but I have long forgotten what they mean.

Cosmic rays are sub-atomic particles ejected from sources such as the sun and other stars in distant galaxies, especially those containing “black holes” which eject very high-energy particles in concentrated narrow beams from each of their “poles”. If one of those beams sweeps across the earth, the cosmic ray telescope readings go crazy!

It’s interesting to note that technology in 1961 was a long way from the technology we now take for granted. Although computers existed at that time, they only existed in worldclass universities and other leading scientific institutions, were monstrously sized and priced and cumbersome to operate. The University of Tasmania and their researchers were poor cousins who only had access to mechanical calculators. On the positive side, these machines provided a better method for calculating than the facilities we had during my earlier university years where we only had access to a combination of brain-power and slide rules. My brother would dispute the existence (in my case) of the first part of that combination.

In the early days of Australia’s operations in the Antarctic, Mawson and the other Australian Antarctic stations used coal-burners as the main source of heat for the sleeping quarters. During the change-over period in summer when the icebreakers arrived to deliver “new” expeditioners and transport the “old” expeditioners back to Australia, we all had to roll up our sleeves and carry hundreds of bags of coal from the ship to store at the base. Nowadays, the stations are all-electric. The US station at McMurdo Sound even had a nuclear reactor providing power.

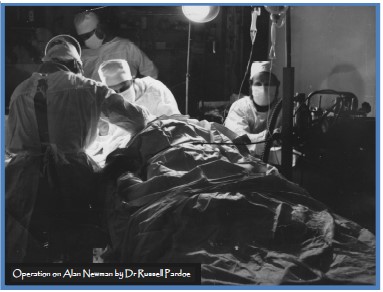

Whilst carrying a bag of coal during the “change-over” period, one of our expeditioners, Alan Newman, suffered a cerebral haemorrhage from which he almost died. We all took turns to nurse him for three weeks until our doctor, following radioed Morse-code instructions from a Melbourne specialist, performed a brain operation to relieve the pressure which subsequently proved to be successful. Even for only one day, looking after Alan, who was semi-conscious and had lost control of all his bodily functions, was an extremely uncomfortable experience for me since I had never nursed anyone before. A picture of the operation under way is shown above. Russell Pardoe was the surgeon, my friend from university days, Rod Hollingsworth, the anaesthetist and the Chief Chef, Ted Giddings, the support nurse.

Several weeks after the operation, our sick expeditioner was picked up from our base by a Russian aircraft and flown back to Australia where he fully recovered. That is, “fully” except he didn’t remember anything about his trip to the Antarctic! During the days leading up to the operation at Mawson, our doctor practiced brain operations on a couple of unfortunate seals to ensure he had the right techniques. I had to bring him those seals since I was the unofficial assistant dog handler and often had to hunt for seals to feed the huskies.

After I returned to Australia and started settling back into “civilised” life, a process that was lengthy (in fact it’s still a “work in progress”) I realised I had deep regrets regarding some of the things I had done. One of those “things” was killing seals in the Antarctic despite the fact that it was done legitimately to feed the huskies. Obviously there’s nothing I can do about it now – what’s done is done – but the memories persist. One memory in particular is of carving the meat into 15x15x15 cms cubes immediately after killing the seal. This had to be done before the very low Antarctic temperatures froze the meat into rock-solid cubes. I was morbidly fascinated by the gruesome discovery that these cubes of meat flinched when touched with the point of a knife. It seemed that the meat itself had a form of intelligence designed for survival!

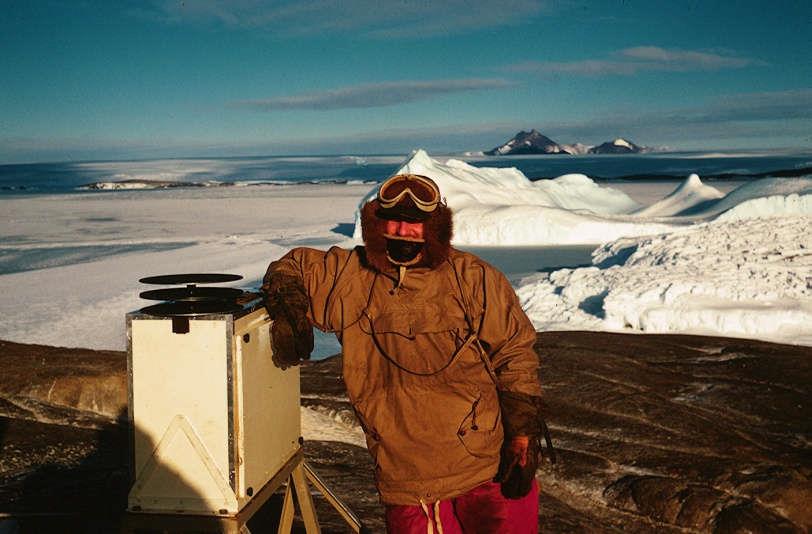

Ian – Aurora Camera 10 miles north Mawson

We had an informal visit by the Russians after the sea ice had melted, this time by a Russian icebreaker which anchored in Horseshoe Harbour. For reasons I forget, I alone accompanied an Australian army officer driving an army DUKW to meet the Russian ship. The officer even allowed me to drive it for a while which was quite an experience – very sluggish response when trying to turn. The ship was crewed with Russians of both sexes – the women all seemed to be very short and fat and wore makeup for the occasion of meeting Aussies. I noted the mess room on the ship was festooned with banners in Russian (obviously) and when I asked what festival they were celebrating, was told by a rather embarrassed crewman they were all political slogans – in the Antarctic for God’s sake – but it was during the cold war!

Although the huskies were extremely friendly towards humans, they were ruthless with each other or with any penguin stupid enough to try and cross the “dog lines” which were about 50 metres from our living quarters. Once, when breaking up a fight between two huskies, one of them accidently bit me on the left wrist – his fangs went right through my watch which saved me from a really bad injury. When he realised what he had done, the husky showed he was full of remorse.

For those of us who loved dogs, the huskies were a godsend, especially when a new litter of pups arrived. Looking after them was a joy and if one of the expeditioners was having a bad day, picking up one of the pups and talking to it soon wiped away their worries. A small number of us formed close bonds with the huskies so when we finally left Mawson, it broke our hearts to leave the huskies behind. As the ice breaker moved out of the harbour at the end of our time, the huskies I had spent so much time with ran along the edge of the water where they could see us leaning on the rails of the ship and barked and howled at us. It broke my heart when I saw them trying to stay with us – they knew we were leaving them behind and I suspect they were equally sad, as only dogs can be sad, when they saw us sailing away. Now, in 2015, those huskies that formed such an important part of my life at Mawson are long since dead. The successive generations of their descendants lived, worked and died at Mawson for another decade or so before those remaining were brought to Australia to retire.

Ian with his favourite year-old Husky

Back in Perth, my brother Kenneth and his wife announced the arrival of their second child they named Josephine, born on 12 October 1961, and dad, who had power of attorney over my savings, purchased (at my telegraphed request) 20 acres in the hills west of Perth for $3,000. Being the wicked capitalist that I was, I resold the block in the 1970s for $56,000. I know that mum and dad really enjoyed driving up into the hills to walk around the block of land, sometimes having a picnic on it – they did this until dad became too sick to drive which probably happened late 1967 early 1968.

Another good friend from St Georges College, Malcolm Hay, was both the Officer in Charge and the Medical Officer at Davis at the same time as Rod Hollingsworth and I were at Mawson – quite a coincidence. Rod and I had a formal celebratory St George’s Day dinner at a separate table in the canteen, with table cloth and candles, served by a waiter – one of the other guys dressed in a dinner suit. The next day, not surprisingly, Rod and I received many insults from the other expeditioners for being so arrogant and pompous!

They were probably correct! The warden at St George’s College during my four years there and for a few years afterwards was the very popular historian academic, “Josh” Reynolds. Josh was the person (described earlier in this story) who was not exactly happy with my behaviour (at times) and fined me for showing a female over the college when such a practice was forbidden. Josh was known, among other things, for his rambling speeches with frequent pauses, ums, aahs, scratchings of his head and mentions of his wife. Each expeditioner was rationed to a limited number of words per year in telegrams they sent to Australia. I used up a large chunk of my “word” rations when I sent a long telegram covering two pages to Josh, coinciding with the St George’s Day dinner at the College. In the telegram, I imitated Josh’s rambling speech with a parallel speech about Mawson, the sea ice, the seals, the weather and anything else that occurred to me at the time. I understand that Josh read the telegram aloud to the undergraduates at the college dinner where it received wild acclaim – my second successful speech!

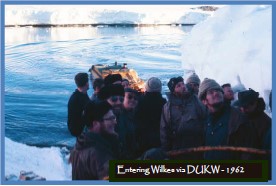

As well as Mawson, the other Australian Antarctic bases operating at the time were Wilkes, Davis and Macquarie Island (Sub-Antarctic).

Expeditions have been carried out every year to the above bases since about 1954 except for Wilkes, which was abandoned in the late 60’s and replaced by Casey Station located opposite Wilkes on the other side of the bay. The old Wilkes base is now totally covered by snow and ice and is no longer visible although the high observation deck might still be visible above the ice in satellite photos from “Google Earth”.

Geographical features within “Enderby Land”, an area west of Mawson, were named after the following Mawson 1961 expeditioners. Two or three other features were named after expeditioners from other years but are not listed in the table below:

| Expeditioner | Position at Mawson | Feature Named |

| Bob Bergen | Radio Operator | Mt Bergen |

| Bob Francis | Aurora Scientist | Francis Peaks |

| Graham Maslen | OIC | Mt Maslen |

| Gunter Weller | Chief Meteorologist | Mt Weller |

| Ian McNaughton | Cosmic Ray Physicist | McNaughton Ridges |

| Ian Todd | Assistant Meteorologist | Mt Todd |

| Keith Brocklesby | Upper Atmosphere Physicist | Mt Brocklesby |

| Rod Hollingsworth | Geophysicist | Mt Hollingsworth |

| Russell Pardoe | Medical Officer | Mt Pardoe |

| Ted Giddings | Head Chef | Mt Giddings |

| Dave Trail | Geologist | Mt Trail |

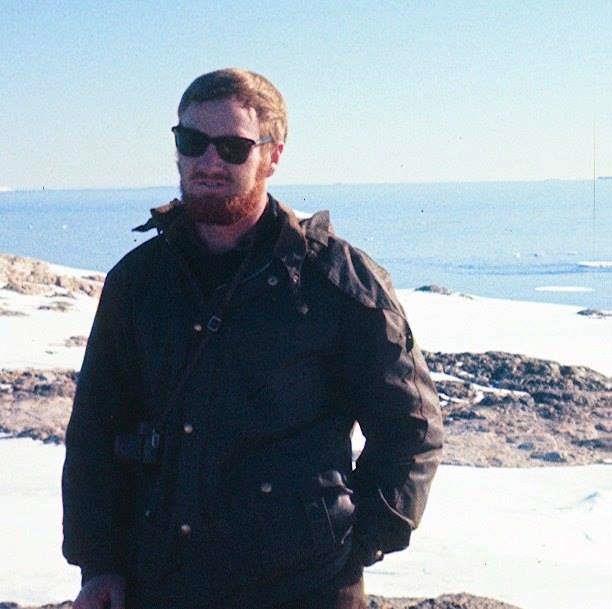

There was never a reason given for assigning the names of some, but not all, 1961 expeditioners to geographical features in Enderby Land. I can only surmise that those whose names were used had made an impression on the OIC during the year at Mawson and possibly on Dr Phil Law (Director of the Antarctic Division) and his wife during the three week voyage down to Mawson on the Danish icebreaker “Nella Dan” in January 1961. Phil and his wife Nell, accompanied half the expeditioners on that voyage, stayed at Mawson for a few nights and then continued with the ship as further surveys of the Antarctic coastline were conducted by scientists before the ship returned to Australia. It’s likely that Dr Law had final say on those whose names were to be used for naming features in Enderby Land.

Reflecting upon my time in the Antarctic, I remember I had thrown myself into all aspects of life, not only at the base but also on the icebreakers during the two Antarctic trips. This possibly contributed to my name being amongst those chosen for naming features in the Scott Mountain Range.

Note the ice breaker, “Nella Dan” was named after Phil’s wife,

Nell.

The feature assigned my name was a set of high mountainous ridges within the Scott mountain range, about 1,500 metres high. They can be seen on Google Earth or Google maps.

Viewing the area of the Scott Mountain Range on the map invokes a feeling of nostalgia because I see “frozen” forever in time, the names of nine of my colleagues – some within the prestigious Scott Mountain range named after “Scott of the Antarctic”.

Enderby Land, which forms part of Antarctica claimed by Australia, is about equal in size to Western Australia – that is, VERY big! Most of it is unexplored, including the Scott Mountain range which includes the McNaughton Ridges which can be found on Google Earth at 67° 28′ 43.77″ S, 50° 31′ 04.46″ E. This feature is definitely on my “Bucket List”.

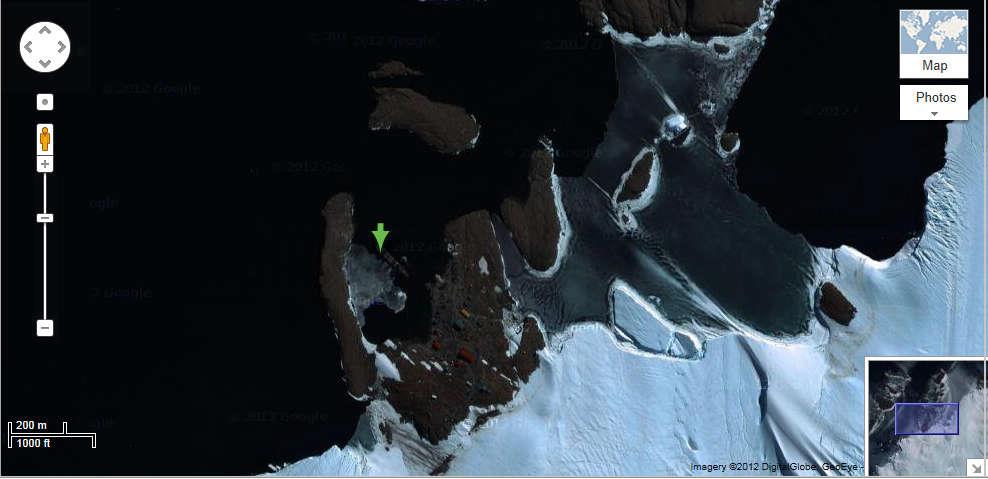

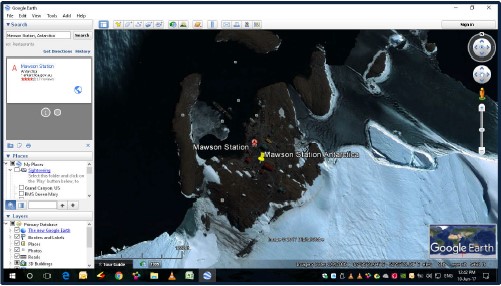

Regarding Mawson itself, input 67°36′ S 62°52′ E to “Google Earth” and zoom in to the arrow pointing to the Mawson base coordinates – then hit the tab “satellite” on the top right-hand side to get the actual photo. When zooming in, keep the locator arrow in the centre of the screen otherwise it will be difficult to locate Mawson because there will be nothing to see except white ice!

In the Google photo below, a ship can be seen in Mawson’s “Horseshoe” Harbour as well as all the accommodation and science buildings on the adjacent land. Zoom out, and the four mountain ranges behind Mawson that some of us visited on the odd occasion for a “holiday” become visible. They are included in some of my photographs.

Satellite photograph of Mawson – taken 2012

To the east of Mawson and visible from the Cosmic Ray hut was a bay called (I think) East Bay. It had a large extension of the ice-plateau intruding into it and when I first arrived, the extension was just part of the ice-plateau. Within a few months, a large crack appeared followed shortly by the extension detaching itself form the ice plateau. A later photo in this section taken from a satellite shows the detached segment as an iceberg. The Google photo below shows the whole of Mawson including the ice-berg still stranded on what must be a rocky seabed

A government website provides information about Mawson Station as it is now (50 years after I was there) and what research is carried out. The website even accesses a webcamera installed at Mawson that provides real-time pictures.

As previously mentioned, I made two trips to the Antarctic; the first was a visit to Mawson in 1961/62 that took a total of fifteen months and the second to Wilkes and a few other places in 1962/63 that took three months. The second visit was to assist a colleague from the University of Tasmania, John Greenhill, with his Cosmic Ray experiments. In all, this added up to a total of 18 months either in, or to, or from, or around the Antarctic.

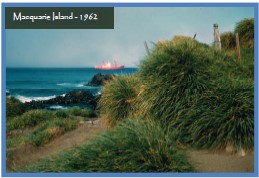

Macquarie Island – 1962

Macquarie Island – 1962

As previously mentioned, I made two trips to the Antarctic; the first was a visit to

Mawson in 1961/62 that took a total of fifteen months and the second to Wilkes and a few other places in 1962/63 that took three months. The second visit was to assist a colleague from the University of Tasmania, John Greenhill, with his Cosmic Ray experiments. In all, this added up to a total of 18 months either in, or to, or from, or around the Antarctic.

During the second trip, the day before the ship was due to leave Wilkes to continue survey work around the Antarctic coastline, my colleague was ashore and I was aboard the ship for reasons I can’t clearly remember but they might have involved my recovery from a party aboard the ship the previous night!

Anyway, a blizzard moved in over the whole region covering several hundred square Kms. It was so cold and the winds were so strong, belting snow at us at over 160 Kms per hour that, for safety reasons, the captain decided to move the ship out to sea. We never returned! The danger of being stuck in the ice around Wilkes for the next 12 months was so great that the captain and the ANARE Officer-in-Charge decided to continue with the survey work along the Antarctic coast line, leaving my very angry colleague behind. I spoke to him by radio from the ship that night and his language was colourful to say the least! In fact, the poor bloke didn’t manage to return to Australia for another six months and even then, the Russians had to make a special trip to Wilkes to pick him up before flying him onto South Africa from where he caught a commercial flight back to Australia.

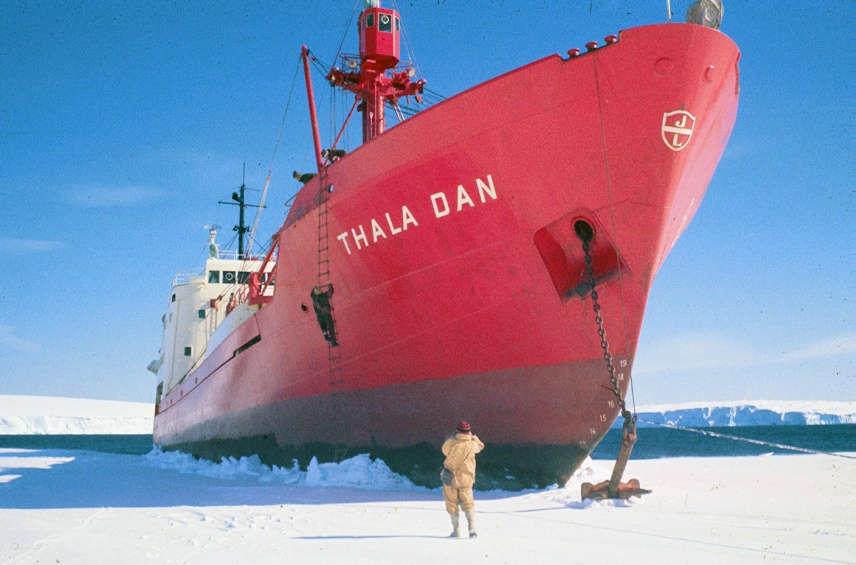

Thala Dan – Icebound – 1963

During our “tour” of the Antarctic coast line and bases, I had an amusing interaction with the Danish captain of the Ice-Breaker. Fancying myself as a marksman (dating back to my National Service days) I was challenged to a shoot-out by the captain. For about twenty minutes, we blasted away at a nearby small iceberg until our honours were satisfied. We agreed it was a draw!

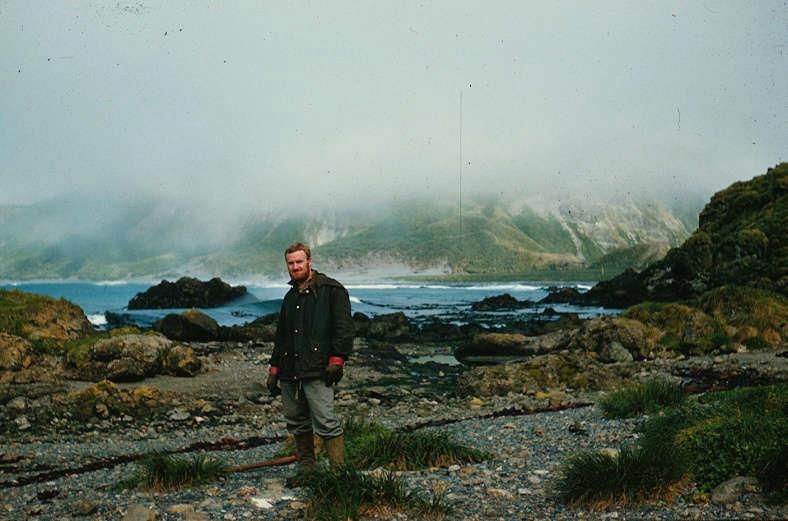

The voyage back to Australia stopped at two other Australian bases, Davis and Wilkes as well as a French Base at Dumont D’Urville, finally stopping at the sub-Antarctic Australian base at Macquarie Island before arriving at Melbourne in March 1963.

One of the features at this French base was a throne-like structure they had constructed for a toilet. The toilet itself was about a metre off the ground with an elaborate structure leading up to it – just like one might expect for a king.

I was lucky to be assigned helicopter duties on this return voyage and, as a result, had quite a few flights in the ANARE helicopter piloted by an ex-RAAF Korean-War Sabre-Jet pilot. This guy was used to taking risks and showed me what a vertical stall-turn felt like in a helicopter. To do this he dived at top speed and a shallow angle aiming straight at the helicopter landing platform on the stern of the ship. About 50 metres from the ship, he put the helicopter into a vertical climb directly above the landing platform. As one might expect, after a while the helicopter stopped climbing and just before it tumbled out of the sky out of control, he flicked it around to point nose-down straight at the landing platform. The vertical dive was frightening but just before hitting the deck, he pulled up the nose and landed gently on the platform.

Landing on Thala Dan – 1963

Thala Dan – Beached – 1963

A couple of times during the tour of the Antarctic coast line, the captain anchored the ship by charging into the pack ice at top speed, running the ship up and over until it stopped then dropping the anchor onto the ice. It was very effective and expeditioners only needed to climb down ladders onto the ice to disembark rather than use the life boats. The photo shows one such occasion.

Living and working in the Antarctic was the greatest challenge I have ever faced in my life, from monitoring cosmic rays to the multitude of other activities in which we engaged, some compulsory, some by choice. For example, each expeditioner had to take his turn at being “watchman” for a 24-hour period. With twenty-five expeditioners, this meant that each one of us was the watchman every 25 days..

What did we do? The number one task was to ensure the safety of the station so that should a fire start for whatever reason, we would raise the alarm and take immediate action to put it out. I have never felt so isolated as I did when on night-watch, walking around the base when everyone else was asleep, knowing the nearest civilisation was another Australian base of 10 men 800 Kms away and that Australia was thousands of Kms away. At night in the Antarctic, especially in winter, dark is REALLY dark with only the light of the stars to see by if one is walking around the distant perimeters of the base.

Not only is it extremely cold but it’s amazing how silent it is and one’s imagination goes into overdrive if one hears a noise coming from some dark area – ghosts of Scott and his men or some large grotesque Antarctic monster with big teeth and a veracious appetite for night watchmen?

During these periods of being the night-watchman, there was always a chance to see the Aurora Australis – and luckily for me, there were a couple of mind-blowing displays. I took many photos, unfortunately only black & white because that was the only film available at the time that was fast enough to capture the action.

Additionally, the “watchman” of the day had to assist the chef, washing up and cutting blocks of snow to melt in a large tank in the kitchen to obtain water. After melting snow for about six months, we decided it was time to clean out the water tank and guess what we found at the bottom? You probably guessed right – husky poo that had been trapped in the snow that we had innocently harvested for water. Amazingly, nobody ever got sick from viruses or bacteria at Mawson – it was just too cold for the little buggers! Luckily, our sense of smell was also diminished because none of us showered more often than once every two or three weeks – or even longer! To have a shower, we had to collect snow, melt it, heat it up on the coal stove in our hut then pour it into a can with holes in the bottom – that was always a recipe for a really fast shower and might be one of the reasons we tended to avoid it.

Another watchman’s duty was to empty the large cans of pee (usually half-frozen) into the

harbour – and you guessed it again – we didn’t have toilets that flushed. Also, every day, one of the four toilets had to be pulled out into the open and the “contents” reduced to ash by setting it on fire using oil and a touch of petrol (if you really wanted to live dangerously). Even with our reduced sense of smell, it wasn’t a particularly pleasant job. Although Weddell seals were the main animals around Mawson, on occasion, a leopard seal would turn up and they were really something. They were aggressive, had rows of very sharp teeth and attacked anything or anyone in their vicinity. They could also move fast so we all learned to keep our distance from them and/or run if we chanced upon one of them whilst walking on the sea-ice.

On another day, a large black Russian aircraft (a Lisunov Li-2) flew low over the camp and radioed us they were landing on a flat area about 10 Kms inland from Mawson. For reasons I don’t remember, I was the only senior officer available at the time and was asked to drive up to the landing strip on the plateau, meet the Russians and help them refuel. I took one of our guys who could speak Russian (an ex-East German) with me in one of the base’s Snow Tracks (the only time I have ever driven a Porsche) and the two of us spent the next 20 hours helping the Russians refuel their aircraft.

It took a long time because none of the available sleds I could tow were strong enough to carry even one 44 gallon drum of petrol (they were all being used on current expeditions) so we had to rig up an old bed frame and tow the drums on it and THAT took a REALLY long time. At the end of the refuelling exercise, I sat in the Russian aircraft while the pilot taxied it along the ice runway in preparation for a later take-off.

My reward – the Russian Pilot’s fur hat!

His reward – my woollen hat!

There were many Russians on the aircraft, the visit from which must have been some sort of PR exercise by the USSR Government, especially since one of them was a Pravda journalist. The others were a mixed bag including the usual cold-war political commissar whose purpose was to keep his eye on the politics and behaviour of the others. We had some great parties with them and one of the photos shows the aftermath – I’m on the right-hand side wearing the Russian Pilot’s hat and the Aurora Physicist, Keith Brocklesby, is on the left. The Pravda journalist who spoke good English was the life and soul of the parties During one party, he gathered about ten of us together and, conducting with his hands in front of our group, taught us how to say “Bolshoi Spasiba” and what sounded to me like “Za vashya zdrovia” in unison. We obliged and even now, many years later, I still remember the lesson. From memory, the first meant “big thanks” and the second something like “you’re welcome” but I could be wrong!

1961 was at the height of the “Cold War” between the Western world and the USSR so it surprised me that the Russians we met and partied with were so friendly. However, as much as I tried, I could never get used to the Russian trick of drinking half a bottle of Vodka at breakfast to counteract a hangover.

We often had a clear blue sky at Mawson and if so, life was beautiful, even if the air temperature was as low as minus 40c. With no wind we could strip to the waist and sunbake with no discomfort. But should even the slightest wind spring up, the chill-factor was a killer. Unfortunately, blue skies were a rare occurrence since most days were overcast and it was often snowing – not vertical snow that we see at the snow resorts in Victoria and NSW but horizontal snow belting into our faces at high velocity due to the constant strong winds.

I volunteered for and was allowed to participate in a “scientific excursion” to an Emperor Penguin rookery on the coast over 100 Kms east of Mawson, led by our doctor, Russ Pardoe (the one who performed the earlier brain operation). While I was away, one of the other scientists, Keith Brocklesby, looked after the Cosmic Ray equipment, after a short bout of training.

The “excursion” was no Sunday drive!

I had to learn how to drive a team of huskies and be prepared to live in a tent for three weeks in mid-winter when the sea was frozen and the temperatures outside and inside the tent went as low as -40c. As a comparison, this was colder than camping inside the deep freeze in your kitchen, but at least a deep freeze doesn’t have blizzards blowing through it! At night, frost formed in our underwear next to our skin and for the whole three weeks, I froze every night, but because I was so exhausted after running all day, I still managed to sleep. And what did I dream about every night? I dreamt of being incessantly thirsty and drinking gallons of clear water – and so did Geoff, the guy I with whom I shared the two-man tent. We didn’t dream about being cold because we had to put it right out of our minds.

Five of us set out with two sledges each drawn by five huskies. We didn’t sit on the sledges because we were too heavy for the huskies – instead we ran along-side the dogs and sledges for the 100 Kms to the rookery and the 100 Kms back to base. For breakfast, lunch and dinner, we ate a special food known as pemmican, which could be likened to a soup made from fat and gravel if viewed from the warmth and safety of the base; however, exposed to severe conditions where the temperature was continually -30c to -40c, the pemmican tasted like food fit for a king.

About two thirds of the way to the rookery the wind speed started to increase and increase until it reached blizzard proportions – a blizzard was defined as snow being blown by winds exceeding 160 Kms per hour continuously for 24 hours. This blizzard lasted five days! After two days, our tents were no longer standing upright – they were flattened. After five days, our tents were a mess -just covered us lying down – we couldn’t stand upright in them. If that wasn’t enough, our radio failed so we couldn’t radio for assistance, not that anyone at Mawson could have taken any effective action. Crawling outside to go to the toilet during that episode took a lot of endurance but of course, we had no choice. Just a one-minute exposure outside the tent at minus 40 C with the wind blowing at over 160 kph was enough to induce rapid hypothermia so toilet “breaks” were necessarily very short, albeit, after many days confined inside a tent, rather necessary. The weird thing is that at the time, as far as I’m aware, none of us regarded the situation as life-threatening – after running with the huskies for many days in extremely low temperatures, we were all acclimatised to extreme weather and the last thing on our minds was that we might die – probably a result of being young and stupid and, like most young people, immortal. It’s only when I look back on episodes such as this that I realise how close we all came to dying.

At the height of the blizzard in the middle of the night, one of the huskies broke loose from the tie-line and, although I didn’t realise it at the time being somewhat preoccupied with staying warm, walked next to our tent, continually brushing against the canvas trying to attract our attention to the fact that he was sick. I was so sad after the blizzard had blown itself out when we found the husky’s body lying next to the tent – he had died from hypothermia. I cursed myself for not doing something about his cry for help – we could have brought him into the tent where he might have had a chance to survive.

After five days the blizzard stopped so we just packed our gear and carried on to the penguin rookery!

As soon as we arrived at the rookery, we started to count the Emperor penguins – our main task. The technique was to form an image in our minds of an area covered with penguins and count the penguins within that area. We then estimated how many of those mental “areas” there were in the whole rookery and multiplied that by the number of penguins first counted. The problem was that they covered such a vast area that I kept losing the “place” where I was counting. After about three attempts, I finally arrived at a figure and we then compared notes, finding that our penguin counts were pretty close to each other, give or take a few tens of thousands!

We then ran all the way back to Mawson with the huskies taking a few more days. Soon after arrival, the doctor treated an enormous blister almost two inches in diameter on my right heel. It was extremely painful.

Back at Mawson – after getting used to operating the cosmic ray telescopes and reducing the time required for their operation, many other interesting activities soon became available for my increased leisure time. For example, several times I accompanied the meteorologists to one of their weather stations located at the base of an impressive mountain range 15 Kms inland from Mawson and known as Rum Doodle. That used to be quite a fun trip, driving or being driven in a Porsche Snowtrack.

On one occasion when I was driving, the chief meteorologist, Gunter Weller, suddenly started yelling at me to stop (he was German and when excited, yelled in German). So I stopped the Snowtrack and asked him why he was yelling. By this time, he was frothing at the mouth, but still managed to yell out something like, “Gott im Himmel, you haf stopped on a snow-bridge” which was a bridge made of snow covering the gaping mouth of a crevasse so deep you couldn’t see the bottom. Driving ever-so-carefully, I edged the Snowtrack over it to safety on the other side. The crevasse was wider than the length of the Snowtrack so had the snow-bridge collapsed, the vehicle would have fallen at least 100 metres and possibly more. Those remaining at Mawson base would have had no chance of finding us or even where we broke through the snow-bridge. Not only that, it would have been impossible for the four of us to escape and we would have been entombed, preserved for thousands of years frozen in a moment of time at the tender age of 22 – a fate worth some philosophical consideration.

On another occasion, the Officer-in-charge of Mawson, Graham Maslen, allowed four of the radio operators to take a couple of days off – providing someone responsible went with them. Amazingly enough, the responsible person was me – a 22-year old. So off we went in another Snowtrack to a nearby holiday resort otherwise known as Taylor Glacier. That was also fun. The hut where we stayed was located close to the edge of Taylor Glacier adjacent to an Adelie Penguin rookery. We recovered a plastic dome from the site and brought it back to Mawson where it was installed as a sky-light on our new recreational building. When the new hut was ready for occupation, the old mess hut was abandoned. I visited the old hut many months later and found the interior covered with thick bright sparkling frost creating a most eerie icy-cold ambience to an area that had once throbbed with life. On the return trip to Mawson from Taylor Glacier, we stopped briefly to photograph the wreck of an RAAF DC3 on the edge of the ice plateau that had been blown from its moorings at Mawson by a blizzard the previous year. Two De Havilland Beaver aircraft were also destroyed by the same blizzard. One of the RAAF pilots tried to “fly” one of the Beavers into the blizzard on the ground but ran out of fuel and had to abandon the aircraft which was then torn apart by the high winds.

As an indication of the trust the OIC had in my behaviour, at my request, he allowed me to borrow his .38 calibre revolver to have a few shots (for fun) at some empty oil drums floating around in the bay east of the base. Luckily for him and the rest of the expeditioners, I didn’t turn out to be a serial killer, but I was disappointed – the bullets couldn’t even penetrate the drums!

What else did we do at Mawson? Well I fished….and I continued to learn how to ski on the snow slopes inland from the base, along with a few other expeditioners. The Chief Meteorologist, a German (the same German as in the crevasse episode) was undoubtedly the best skier. He taught me how to sing (in German) the WW2 Wehrmacht song, “We’re marching against England” – “wurden marschieren gegen England”. It used to annoy hell out of the only Pommie we had at the base!

We watched movies – we had about ten movies and we watched each one so often that the projectionist had no need to turn on the sound-track – we knew all the words. One of my favourites was a 1950s musical with Fred Astair and Cyd Charisse called “Bandwagon”, and at our Christmas party, a few of us re-enacted a scene from it substituting our own words! Quite amusing!

We had a truck and motor bike at the station. On one occasion, a couple of us drove the truck onto the frozen sea and had a competition to see who could do the most “whirlies”. To do a “whirly”, one had to accelerate to a high speed heading out to “sea” (it was all frozen) and then throw the truck into a full-lock turn. The truck then slowly but surely performed an elegant “ballet” of “whirlies” until running out of speed. This fun continued until one of us (not me!) “whirled” the truck into a crevasse in the ice where it stayed for a few days until our mechanic worked out how to recover it. We used the motor bike for a number of activities, one of which was to tow somebody on an old aircraft ski on the sea ice and execute a few more “whirlies”. Not something our mothers would want to know about. That was definitely frightening, especially if you were the one sitting on the aircraft ski.

From our very first day at Mawson, acting as a step to the supplies hut was an unused JATO bottle brought to the base when it was first constructed. JATO is an abbreviation for Jet Assisted Take Off, a device which when used, is strapped to an aircraft like the DC3s used by ANARE, to provide extra boost when taking off from (say) a short runway. I had eyed-off this JATO device for some time with the intention of strapping it to a sledge, sitting on the sledge and starting the JATO. Fortunately for me, the opportunity never arose because had I carried out my ill-conceived plan, I would likely have transported myself several Kms at very high speed over the frozen sea with little chance of survival! It wasn’t the first time one of my plans failed to materialise which probably accounts for the fact I am still alive.

The voyage home took longer than most of us had anticipated because of the number of Antarctic bases and other locations the ship visited.

Well I guess that’s about it – apart from the final night on board the Thala Dan before arriving at Melbourne in January 1962 when we had a boisterous but rather sad final party anchored somewhere in Port Phillip Bay.

Of course, there was further three month trip to the Antarctic scheduled for later in 1962 to assist John Greenhill in balloon-borne cosmic ray measurements at Davis.