Australia’s Antarctic Rebuilding Program at Mawson

By

Bob McEwan, Chief Structural Engineer, Australian Construction Services

1979-1987

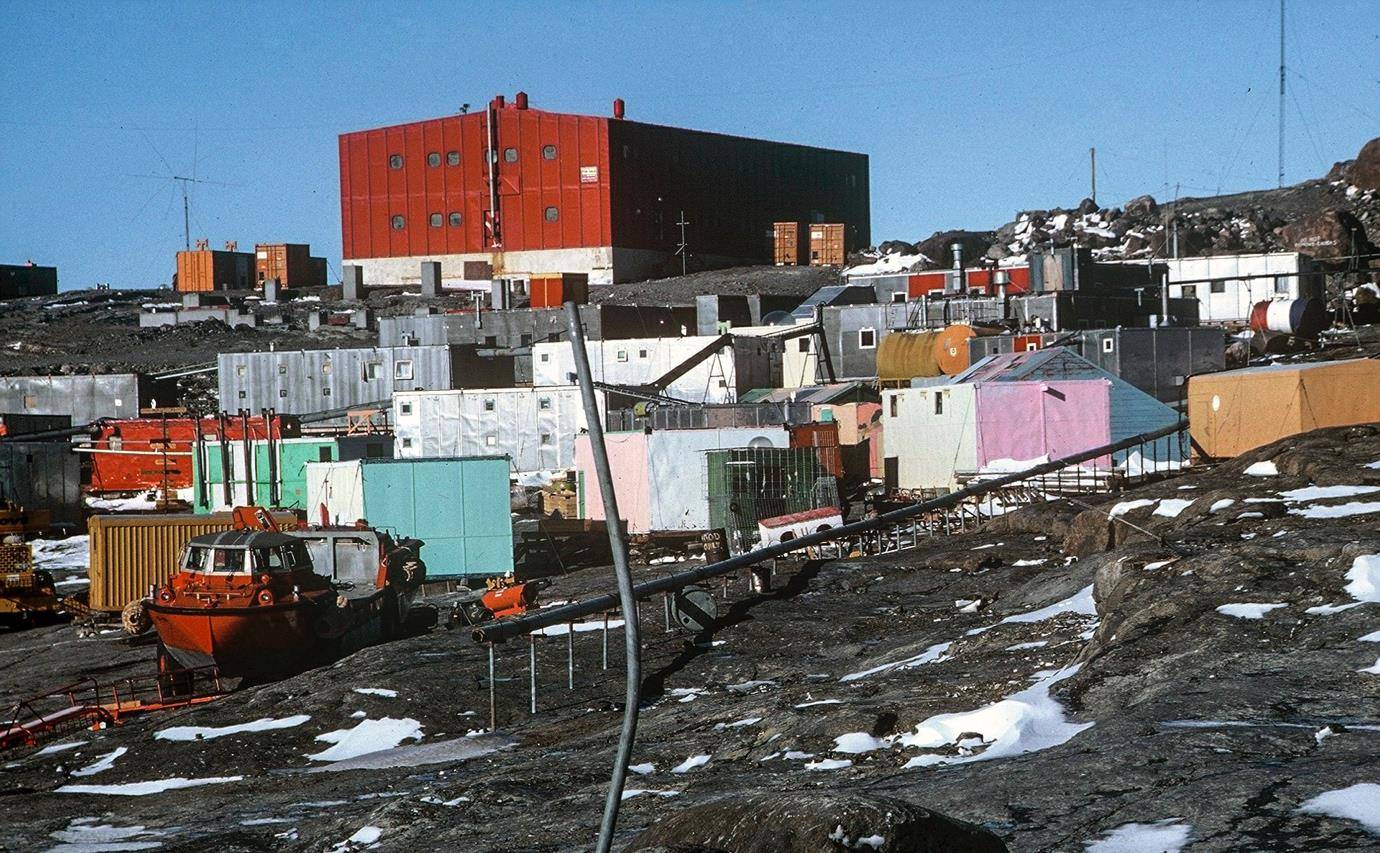

Looking east, Red Shed Living Quarters dominating, with Jocelyn Island in b/g. © AAD by Brett Free

Mawson Station – After the Re-build

THE SETTING

The building site at Mawson Station is in a truly awesome and beautiful location, but subject to some of the most challenging environmental

conditions on the planet. It’s located on a coastal ice-free granite outcrop where the temperature ranges from -40deg C to +5deg C with air of a very low specific humidity. The site is subjected to winds of up to 280kph, which carry fine dry drift snow. Access to Mawson is by ship for 3 months during summer when the sea ice temporarily breaks up.

Mawson at the edge of Horseshoe Harbour. Late summer, circa 1960, with plateau in background.

© Ian Bird, 1960 collection

THE OLD DAYS

The building design philosophy for Australia’s Antarctic Stations has been continually developed since the establishment of Mawson Station in 1954. The features of these early buildings were:

• relatively small.

• load-bearing insulated panels with external guys.

• located directly on the ground and designed for rapid erection by expeditioners during the short summer season.

• the designs suffered serious short comings, including inadequate vapour barriers (resulting in many panels rusting out from the inside), inability to replace damaged external panels, noise and vibration problems, access difficulty for snow clearing equipment due to the guys, congested sites leading to snow drift problems.

By the mid 1970’s, the buildings and services had deteriorated to an unacceptable standard and many of the older buildings were beyond repair. The standard of accommodation had become inadequate for permanent stations and living conditions were small, cramped, lacking in privacy and in many cases, a fire risk.

The Old station – blowing drift was typical during the summer of 85/86 when the

construction crew had day after day of strong katabatic winds. © Bob McEwan

Whilst a program of rebuilding Australia’s Antarctic Stations began in 1976/77, it was not until 1981 that the Australian Government gave approval to redevelop the three stations. Australian Construction Services (ACS) was responsible for the design, fabrication, construction and commissioning of all facilities, whilst the Australian Antarctic Division (AAD) was responsible for the provision of logistical support and for the operation and maintenance of all completed facilities.

The Red Shed – Sleeping Quarters and Medical Surgery – completed 1984. © Bob McEwan

In 198I, as Chief Structural Engineer, I formed a team of excellent engineers and set about the urgent task of completing a program of research, testing and development, including developing an Antarctic Design Wind Code, completing essential site investigation and ground anchor testing, cold region concrete technology, cladding panel testing, development of a Design Manual, specifications, a Construction Manual and a specialist training program for each year’s intake of tradesmen. Unfortunately, we weren’t given the luxury of undertaking this essential work prior to commencing the design and construction of the new Australian Antarctic Building System (AANBUS) buildings, resulting in structural modification works being required to the very early AANBUS buildings. In fact, until 1981, the AANBUS buildings were funded on a very ad-hoc basis, with no funding for any essential R&D!

Erecting cladding for Mawson Store 85/86. © Bob McEwan

Pouring concrete for typical slab on ground. © Bob McEwan

THE RE-BUILD PROGRAM – DESIGN FEATURES

The main features of the unique AANBUS building system include the following:

• larger and more efficient buildings.

• braced steel framed structures on reinforced concrete footings, anchored to the ground, without the need for external guying.

• external fire-retardant insulated sandwich panels which are durable and easily removed for maintenance. They are finished in silicon-modified polyester enamel or with chemelex abrasion resistant coating in bright primary colours.

• windows are triple-glazed factory units which are generally fitted into panels during fabrication.

• provision of vapour barriers on the inside and moisture barriers on the outside of buildings, and the prevention of “cold paths” (a pathways for low temperatures to gain access to inside the building leading to condensation and corrosion).

• maximum use of standard and prefabricated components, within the constraints of the available shipping and material handling facilities, noting that there was no wharf at Mawson.

• simplified construction details to minimise the extent of site labour during the brief summer outside construction period (3-4 months).

Drilling in preparation for grouting ground anchors. © Bob McEwan

Concrete footings for Living Quarters extension to the Red Shed. © Bob McEwan

• In situ concrete is minimised using precast concrete and ground anchors (instead of mass concrete).

• a comprehensive quality control program was used to successfully mix (using pre-mix concrete), place and cure concrete in temperatures down to as low as -10 C.

• trial erection of building structures in Australia to minimise the risk of delays to construction work on site.

• careful location of buildings to minimise the drift snow problem. All buildings (rectangular in plan) are oriented with their long sides parallel to the prevailing (strong) winds which carry the drift. Doors, windows and openings are only permitted on these sides, and the drift snow generally accumulates at either end of the building and tends to blow clear on the sides.

• fire prevention and control.

• site services connect the heating hot water, potable water, firefighting water, sewage, electrical and communications to the station buildings.

• the reticulated pipe system is supported above ground for ease of maintenance and insulated and heat-traced (using a heated wire) to prevent freezing.

Above ground site services from melt lake. © Bob McEwan

With a complex system of services to each building – electricity, waste heat, drainage, fresh water – servicing is made easier with everything above ground level. Here Geoff McDonough at work on site, 1996.

© AAD by Kerri Darby

• power is generated in the main Power House using diesel powered generators, along with an Emergency Power House and now supplemented by wind powered turbines.

Power House. © Bob McEwan

THE DESIGN TEAM & SUCCESS

Despite all the challenges and the obstacles placed in our path, my role in the Antarctic Rebuilding Program is a highlight of my long career as a Structural Engineer and Project Manager. I was fortunate to enough to present several papers on this unique project, including one to an International Conference on Cold Regions Engineering in Vancouver in September 1984, where the Australian Antarctic Building System (AANBUS) was recognised as an internationally accepted benchmark in Antarctic and cold region design. Special credit must be given to the AANBUS Architect, the late Phil Incoll, for his pioneering work.

Whilst many of the AANBUS buildings are over 30 years old, they have performed extremely well. In fact, they should have an indefinite lifespan, with only the cladding panels needing to be replaced at some time in the future (which is quite an easy task).

TRANSPORT TO MAWSON & FIELD CONSTRUCTION

In 1984 a new ship, the Icebird, was leased by the AAD, allowing for the handling of larger cargo and clearing the way for a new modular building concept, based on shipping container technology. This AANBUS Modular Design is ideally suited for electrical and mechanical installations and smaller buildings.

Icebird MV moored in Horseshoe Harbour, 1989 – a German built and designed ice-strengthened ship, for carrying passengers and cargo, made her maiden voyage to Antarctica from Cape Town in November 1984 to cope with the building materials for the re-build program.

© AAD by Alan Arthur Wilkinson

I was intimately involved in the Antarctic Rebuilding Program from 1979 to 1987, as the Structural Engineering Team Leader, responsible for R&D, design, tendering, procurement, trial erection, tradesmen training (including trial erection of a mini AANBUS building), construction, commissioning and handover of buildings and services at Australia’s three Antarctic Stations. I completed a round trip to Macquarie Island, Casey, Davis and Mawson in 1983/84 on the Nanok S and was Construction OIC at Mawson in 1985/86, visiting Heard Island on the way down on the Icebird and returning on one of the last voyages of the Nella Dan!

Whilst I designed the Mawson Store, Mawson Power House and Mawson Living Quarters, I managed the design of all the AANBUS Buildings during the period 1979-1987.

The role of Construction OIC at Mawson was particularly challenging and satisfying. Some of the key experiences and learnings include:

Icebird beset in pack ice, 1984. © Bob McEwan

• I was a Structural Design Engineer and had never managed a construction site before and had received no management training to prepare me for my new role.

• I was the last to board the chopper on the Icebird to fly into Mawson from the ice-edge, without realising that they had grossly overloaded the chopper with “essential building materials”. As it approached Horseshoe Harbour at Mawson, the chopper started smoking badly and landed very heavily, never to take off again all summer – so much for safety.

• No sooner had I disembarked at Mawson after a 4-week voyage on the Icebird, the ACS Foreman greeted me, inviting me to come for a run with the huskies. I naturally accepted and jumped on the sled. He promptly reminded me that this is not the movies – here we run with the huskies and only the gear is carried on the sled! We ran half way to the Auster Rookery and back and I didn’t recover for at least 3 weeks! I then realised that I was being tested.

Nella Dan at Mawson, February 1986 – re-build in full swing. © Bob McEwan

Bob McEwan (rear), out with the dogs on the first day at Mawson.

© Bob McEwan

• The next day at our Team Meeting I was again tested – I was greeted by some Winterers who, after 12 months, had had enough and wanted “out” – they were certainly not interested in listening to some motivational speech from a Structural Design Engineer on how important it was to put in another 4 months of hard work.

• In the first weeks I was tested many times! On one memorable occasion, after a few beers one night I returned to my donga to find a frightened skua had been placed inside. After many attempts I managed to capture the skua, but only after it had sprayed my donga with massive output from all orifices! Although I wanted to hang the culprits, I maintained my calm, passed the “test” and there were no further incidents all summer.

• The weather was particularly bad that summer, forcing me to tear up the construction program and replan the summer, with almost no communication with the Australian Office – satellite communication was almost non-existent in those days.

• People management and communication are critical skills when you have little or no support – I quickly realised that the only way was to lead by example.

• Teamwork and team morale are critical in this difficult environment.

• When the wind dropped, it was heartening to see the men willingly volunteer to work late into the night on the Mawson Store. As I had no means of rewarding them for their dedication, I found that giving them additional days off to undertake trips was highly appreciated and the recognition did wonders for their morale and productivity. We all knew that we may never come this way again and our trips to Rumdoodle, Mt Henderson and Auster Rookery were highlights of our stay.

• No-one understood the importance of safety in those days – we all stood on top of the Mawson Store in moderate winds installing roof panels, without safety harnesses! We survived that summer without any serious accidents – a miracle.

Constructing bridge near Trades building, 1996. © AAD by Kerri Darby

Roof of Mawson Store – in those days, safety was not a priority. © Bob McEwan

• I asked the one foreman whom I particularly respected – what is the single most important task to be completed this summer? He immediately replied that ACS (Australian Construction Service) needed to commission and hand-over some of the long-completed buildings to the AAD (Australian Antarctic Division). ACS hadn’t developed and agreed commissioning and hand-over procedures with the AAD and the AAD were in no hurry to take them over as they would then have to assume responsibility for their operation and maintenance! In the meantime, ACS tradesmen over the winter had to spend most of their time on maintenance issues.

• I naively thought that the building materials that were delivered 1 -2 years earlier would be easily located – wrong! They were either buried under drift snow or went missing! I soon realised that the storage areas resembled an “open-air Bunnings” – expeditioners over the winter had been busy using our building materials to make furniture and equipment, which they loaded onto the ship in custom-made RTA (Return to Australia) boxes.

Footings of new Trades Workshop at Mawson, 1996. © AAD by David McCormack

Winter build-up of drift snow. © Bob McEwan

LASTING IMPRESSIONS OF MAWSON

As I reflect on my time on the Antarctic Rebuilding Program, some other memories that come flooding back include the following:

• On arrival at Mawson in 1984 I was horrified that the standard waste disposal strategy was to place the rubbish (including styrene foam, plastic garbage bags etc) on the frozen sea ice during the year and wait for the thaw – the fragile environment just didn’t rate in importance.

• As the contractors in Australia had supply-only contracts, with no responsibility for construction in Antarctica, trial erection of building structures in Australia was essential to minimise the risk of delays to construction work on site. Despite my strong objections, the bureaucracy decided that to achieve some minor budget savings we would in future only trial erect 1/3 of each structure. What a terrible decision that turned out to be, resulting in the other 2/3 of the structure being a nightmare to erect in Antarctica.

• Logistics was always a lottery! On my round trip in 1983/84 the building materials were loaded into the cargo hold in the reverse order of the trip, i.e., Mawson, Davis, Casey. No sooner had we departed than the decision was made by the AAD and ship’s captain that that itinerary order was changed to Casey, Davis, Mawson, causing huge problems at Casey as their urgently-needed materials were in the bottom of the hold.

• After Casey, the Nanok S called into Davis on our way to Mawson. At Davis it was discovered that the fuel hoses were too short and essential fuel deliveries could not be made! Not a problem, shouted one enterprising expeditioner as he located some old discarded hose in the tip! We were dismayed to watch this old “soaker-hose” spray diesel fuel over the pristine ocean.

• On another occasion when I questioned the delay to the shipping schedule, the Captain informed me that the ship would run like clockwork, if it wasn’t for the bloody expeditioners and cargo.

• It was unfortunate that the Rebuilding Program faced opposition from some quarters of the AAD, due to the mistaken belief that it was taking away funding from the Science Program. I always felt that the AAD leadership didn’t do enough to explain that both Programs were separately funded and that the whole purpose of the Rebuilding Program was to provide first rate functional facilities to support the Science Program.

Foreshore rubbish tip area, 1984. © Bob McEwan

CONCLUSIONS

Some of the things that I believe should be done differently next time are:

• Ensure that the AAD and ACS work closely together in a collaborative manner.

• Ensure that no design is commenced until the necessary R&D is completed (to do avoid unnecessary re-work).

• Ensure that a safety culture is a top priority.

• Respect the pristine environment.

• Ensure that leaders receive adequate training and support.

Whilst I am so proud to have been a key part of the Antarctic Rebuilding Program, I just hope that with the demise of ACS that all the valuable IP (Intellectual Property) we developed has not been lost, or buried at the bottom of some storage container at the AAD’s headquarters in Kingston?

© Text Bob McEwan, Chief Structural Engineer, Australian Construction Services. 20th February 2019.

Aerial view of station looking towards East Bay, 2014. © AAD by Daniel Suttle

The Australian Construction Services Site Team, 85/86. © Bob McEwan

Bob McEwan with Icebird at the edge of the ice on way to Mawson, 85/86. © Bob McEwan

Aurora Journal Spring 1987

Aurora Journal Spring 1987