Brian Brawley ANARE Club representative Polar Bird 1995 – 1996 season

At Wilkes looking towards Casey. Photo Brian Brawley

On January 15th I966 I was in the mid-north town of Jamestown getting married to Liz; now 30 years later where was I celebrating our 30th wedding anniversary? On a plane heading for Hobart and a seven week round trip to Antarctica, that’s where.

In 1982 I had spent twelve months working at Davis, the most southerly Australian station in Antarctica. On my return I joined the ANARE Club and plotted ways to try to return to

Antarctica if it was at all possible. One avenue, besides the hard work and long haul of another year working for the Antarctica Division, was through the scheme where the Division sponsors one active ANARE Club member on a PR round trip. Each year I envied the member who was selected, and finally in I994 the SA branch of the ANARE Club agreed that my name should go forward. Good news / bad news time, I was not selected but was first reserve. The selected member did not break any legs, fall victim of foul play or pull out of the trip and I thought my chance had passed me by. But good fortune was on my side and my name was put forward again the following year. This time my “ship came in”, with all bells ringing, as the trip, which normally lasted 3-4 weeks was going to be for seven weeks this year.

So there I was in Hobart, on my wedding anniversary, getting kitted out with the fondly remembered cold weather gear. It was summer time in Antarctica. That means temperatures

about zero (almost shorts and T- shirt Weather). Heavy winter gear would not be required. There were familiar faces to be caught up with (last seen in those ‘82 days) and the ‘red taxi‘ at the wharf to view. In 1982 I had returned to Australia on the most famous ‘red taxi‘, the MV Nella Dan (now on the bottom of the sea off Macquarie Island). This time I was to voyage on the MV Polar Bird, formerly the Ice Bird, a Norwegian ship of 6,100 tons. The Polar Bird is some three times larger than the old Nella Dan, but in comparison to most ocean going liners she is still very small. She is an ice strengthened cargo ship, with an extra accommodation module situated over the Number 3 hold, and has a 19 man crew who were mainly Norwegian or Polish, all of whom spoke English. Also on board were 38 Australian expeditioners, including some ‘round trippers‘ – like me.

We were supposed to sail on Wednesday, I7 January and on that day we underwent the mandatory safety and life boat debarkation drills – if you don’t show for these drills, then you don‘t sail and that’s that. Things did not go according to plan, and it was not until 7:30am Thursday, 18 January that there was a commotion on the dock involving hand shaking, waving, glassy eyes and some streamers. Finally we sailed – on a beautiful sunny day with blue skies and calm seas heading for the voyage of a lifetime.

The ship‘s complement being light, my four berth cabin was occupied by only two. I was extremely lucky to have as my companion the Assistant Director of the Russian Antarctic & Arctic Division, Valery Klokov. We shared many a long conversation and found we had much in common. When you talk with highly regarded people from another culture you become aware that the troubles of the world are so often those of power and politics, that people are really so very similar. In South Australia we are used to being part of an integrated society, so often strangers turn out to be connected to us, they know people we know, work at the same types of occupations, share the same interests etc, etc. It can quite take you back when you find the same thing happening with a stranger from another land – Valery and I are the same age (our birthdays are only a couple of months apart), our wives were born in

the same year, my wedding anniversary is the 15th January, his is on the 12th January. We each spent our 30th wedding anniversary heading for Antarctica, our eldest children were born in the same year – but then the pattern breaks; I have two other children (all within 3 years) and his second. and last child, was not born until 12 years later. “I am a very slow thinker“ is his explanation!

By midday on the 18th January we were in the great Southern Ocean and pushing into high seas. Luckily we were taking the waves nose on. This meant that we were only pitching and

this is much easier for the stomach to handle. Later in the voyage we were to take seas side-on and the rolling started. The ship would roll to over 30 degrees either side of centre, though truthfully this is only moderate for these seas — they are not called the ‘Roaring Forties’ without good reason! Mind over matter, or a cast iron stomach, saw me queasy but I am proud to boast I did not miss a meal; many ‘new chums’ were not so lucky. We all missed many hours of sleep though as it is almost impossible to do this when you are either being ‘brained’ or jarring your feet as you slide from one end of your bunk to the other.

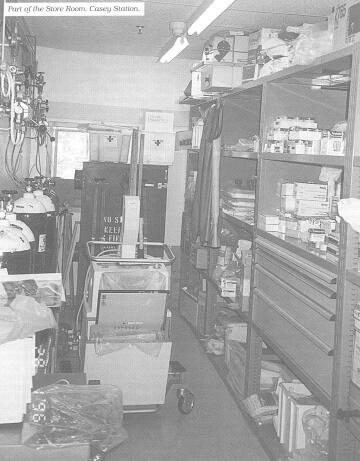

After five days on the high seas we reached the pack ice. We sailed past the Petersen Bank, an area of shallow water (100—300 metres deep) where a large number of icebergs run aground – some as big as the city of Adelaide – and ‘Mr Kodak‘ made a fortune as cameras and videos of every make and model were given their first real workout. By midnight on the 25th January we were dropping anchor in Newcomb Bay at Casey Station. Thus, whilst you were all relaxing on the Australia Day holiday we were unloading supplies. The purpose of this voyage (besides giving me the experience of a lifetime) was to do the major re-supply of the stations in Antarctica. Most of the supplies are packed in large sea containers of between 10-17 tonnes which are lowered by crane onto barges and then taken ashore to the stations to be unpacked — okay when the sea is calm but somewhat hairy when the sea is running and you are trying to GENTLY land a large heavy weight onto a moving and what appears to be a somewhat fragile barge. These supplies were all the things required by the station for the next 12 months including frozen meat, fruit and vegies, other foodstuffs, soap and toiletries, clothes, electrical spares, pumps & spares, machinery parts and scientific equipment. Work completed, we had time to look around the new station. The old ‘tunnel’ station that I had seen in 1982 has been completely removed.

Part of the Store Room, Casey Station. Photo Brian Brawley

Sunday, 28th January, saw us pushing our way out through the pack ice once more, heading for Davis some 900 nautical miles away. The weather was overcast and somewhat foggy, but

due to the latitude and ice the sea was calm. Once again ‘Mr Kodak’ rubbed his hands as many ice floes (populated by penguins and seals of various species) were sighted in the sea, as were numerous whales. We also sighted our own Australian Antarctic ship, the MV Aurora Australis, which was involved in an extended oceanographic survey. The ‘Aurora’ was to spend several months zigzagging through the great Southern Ocean whilst we did the ‘hard yakka’ – and saw Antarctica. Somewhat late, a special dinner was held on board to mark Australia Day – and to mark the crossing of the Antarctic Circle. Some passengers dressed up in true dinner gear; others let their hair down in true Aussie fashion. The food on board was absolutely great, there was only one problem and that was to know when (and how) to stop eating!

Midday on Friday 2nd February saw us in sight of the Vestfold Hills and Davis station. Davis holds a special place in my heart, it was there that I spent 1982. When I was being

interviewed for that position I was asked if I had a preference for any station, I said “Not really, but would rather not go to Macquarie island as it was only halfway. If I was going South I wanted to go as far as possible”, and so they placed me at Davis.

Operating Theatre Davis Station. Photo Brian Brawley

Hospital Accommodation at Davis Station. Photo Brian Brawley

The next morning, as I explored Davis, memories of 1982 flooded back. They were in stark contrast to the reality of the new station. Australia has spent millions of dollars in the past 15

years rebuilding all the stations, and the living facilities are now as good as any better motel in Australia. Gone are the dongas [sleeping boxes big enough for a bed, small wardrobe and smaller desk], the gas-fired toilets [crappers) and cramped living quarters (LQs] in which meals were taken. They have been replaced by spacious ensuite rooms [with running water) and large comfortable (almost luxurious) LQs. Gone are the scheduled radio-telephones that made your voice sound like Donald Duck [provided that there was no ‘hole in the sky’ which meant no call at all). Each room has its own telephone and fax point, as have all the workshops, so that now you can ‘call home’ anytime. Because of the major maintenance schedule, and a big scientific program, Davis was a little crowded with 96 personnel on the station – the most we ever housed was less than half this number. Just like Casey there was work to be done and

the supplies had to be unloaded before we could set sail again on Sunday, 4th February.

From Davis we headed for Law base, situated (at latitude 69.205, longitude 76.2115) some 80 nautical miles away in the Larseman Hills. The Larseman Hills area houses three other stations, two belonging to Russia (Progress l, currently unmanned, and Progress 2 which is manned all year round) and the Chinese Zhong Shan Station which is also manned all year. Progress l & 2 were a major reason for Valery‘s visit – my cabin mate, remember? Our main task was to offload supplies of food and fuel for Zhong Shan. The ship stayed some four kms offshore, in the pack ice, and the supplies were all ferried inland by helicopter, a job that was scheduled to take two days but it was completed by teatime. With time up our sleeve we set sail for Sandefjord Bay on the eastern side of the Amery Ice Shelf. This is an area that has to be seen to be believed. The Amery is where the Lambert Glacier (the largest glacier in the world) meets the sea. The sheer size of the ice shelf and glacier is awesome. It extends for kilometres – but it is one huge ice cube! Large crevasses are visible along the face and top of the glacier. These split and huge chunks of ice break off to float away and become the icebergs that we had passed. The whole glacier is continually moving and emits a growling noise that is clearly audible. We were not there just for the scenery, once again supplies had to be unloaded. This time it was 200 litre drums of fuel that had to be cached 25 kms inland, ready for a traverse next year. Once again the helicopters were used, and once again the job was completed in less than the scheduled time. The helicopters also had to go inland over the ice shelf to Beaver Lake, in the Prince Charles Mountains. There being a few spare seats in the chopper, I scored a ride. This was the trip of a lifetime. The Prince Charles Mountains are a prestige area of Antarctica and only a privileged handful of people have ever been there. It was truly the highlight of the entire voyage. My video camera ran hot trying to record the trip and the spectacular views.

At midnight we set sail for Mawson. On the way we stopped to pick up some hydrographic equipment placed on the ocean floor some 12 months previously and programmed to record ocean currents. Thanks to modern technology, using satellite navigation equipment etc, we were able to locate the first set of equipment and release it via a sonic signal. The second set of equipment proved to be more elusive and after some time it was decided to recheck the original pencil entries in a notebook. Guess what? The wrong co- ordinates had been entered into the computer. The captain steamed to the new co-ordinates and once again the equipment was recovered. It seemed that someone was really looking after us on this trip. The ‘Bios’ had been hoping to recover one set of equipment; to get both was a real coup. On we sailed in first class weather – blue skies, no wind and crisp air (only -8°). We manoeuvred between icebergs through the region known as Iceberg Alley and soon sighted the mountains on the plateau behind Mawson. Mawson has a small horseshoe harbour which is entered via a natural channel, the Kista Strait. Manoeuvring into this bay took some doing. The ship tied up to bollards cemented on the shore and back to work we went unloading tonnes more supplies. On the third day we unloaded (pumped) ashore 600,000 litres of special diesel fuel for use by the station through the following year. We had arrived at Mawson four days ahead of schedule, and now with our work completed we had time on our hands to explore more thoroughly. We could not sail until our scheduled date as we were to take back returning expeditioners after their stint in Antarctica and some had yet to complete their work whilst others were still out in the field.

Mawson is probably the best known of all of the Australian stations, particularly with the publicity surrounding the return of the huskies in recent years. This was my first visit so I was not privileged to see the living dogs, however the station is still steeped in the ‘dog culture’ with mementos and references to them throughout the LQ. An expedition was arranged for us so that we could travel to the nearby Mt Henderson, approx 30 kms inland. This was another real treat, even though the weather was a bit cool -18° and 30+ knots of wind. The low temperatures are normally not a problem, it is possible to stand outside in Antarctica in shorts & T-shirt (and big boots) on a sunny day and in temperatures about the zero mark! It is the wind and moisture that make you feel the cold, and on this trip many ‘new chums‘ experienced this coldness for the first time – not that it stopped them from going and enjoying the trip.

New Mess at Mawson Station. Photo Brian Brawley

On the return trip it was decided that ice was required for the evening drinks and not just any ice would do. We stopped at a region of ‘blue ice’, this ice is extremely hard and thousands of years old. It was quite funny watching people trying to use pickaxes to chip away fragments of this ice. Their actions ranged from the fully fledged over the head swing from the fully vertical position, to ‘henpecking’ from only a few inches – head down bum up. Nevertheless ice was obtained, scooped into a container and duly deposited into the required drinks that evening.

After unloading all those tonnes of supplies along the coast it was now time to reload and turn around to make the return trip home. The Antarctic Treaty, to which Australia is a signatory, states that all waste must be returned to the ‘parent’ country – excepting some paper and wood that may be incinerated by a high temperature process. This is great for the environment. Prior to this treaty the stations dumped their rubbish in any convenient nearby position – and we all know what landfill looks like. Smell is not a real problem – there is very little decay due to the low temperatures, but RTA [Return To Australia] certainly helps keep the place in a pristine state. So the Polar Bird became a gigantic rubbish ‘truck’ as container after container was filled with used equipment, broken machinery and all types of rubbish.

Exactly one month after leaving hot Adelaide we were hit by our first blizzard, not a real doozey as it only lasted l5 hours and no real damage was sustained; they often last days and can create real havoc. By midday the next day (Friday, l6th Feb) we were sailing the return leg; on board were 15 expeditioners from Mawson. They had spent the last year, or up to 15 months, in the South and were now heading home. It was a strange feeling watching their faces, and listening to their experiences and plans of things to do on their return to Aussie. It brought back memories of how I felt 15 years ago and it made me realise that in three short [or long) weeks I too would be home. The weather had cleared and was once again beautiful as we headed back to Davis where we were to pick up 13 Chinese expeditioners from Zhong Shan, 28 expeditioners from Davis and tonnes more RTA rubbish. Once again the weather changed and we were caught ashore, unable to get back to our beds on the ship. We spent that night on the station, sleeping in any vacant spot we could find. The cooks were up early the next morning to make extra bread for everyone when they accidentally opened both large oven doors simultaneously. The resultant gust of hot air set off the heat detectors and the wail of the fire alarm jolted everyone from their sleep. Being a ‘vollie firie‘ from way back I acted instinctively and tumbled from my bottom bunk to scramble into my clothes. Unfortunately the person in the top bunk was a little slow (or fast) and before I had cleared the area had landed on top off me – he was no light weight either! This reinforced another recent change in ‘how things are done’. In my day we would have all had a good laugh at the mustering station and that would have been the end of the matter. These days that alarm would have been monitored in Hobart at the same time as the incident was occurring – shades of big brother watching! We sailed from Davis late in the evening of 20th February. I have some great video of that night – the sea was glassy calm and, at about 10 pm, the sun was just dipping to the horizon as the moon rose on the opposite horizon – magical.

A Week after leaving Mawson we were on the sea again, heading for Casey and participating in a real Aussie barbecue – with a difference. We were on the back deck of the ship and the temperature was -10 (you don’t have to be mad, but it sure helps] but the food, drink and Aussie spirit more than made up for that. We arrived outside Casey station late on Saturday night too late to dock. and tied up at 7 o’clock the next morning. Once again we had tonnes of garbage to load, but as at all the stations there was still time to make friends and explore the nearby area. After tea one evening we decided to visit the nearby Wilkes station. This station was originally built by the Americans for the International Geophysical Year (1957-58). It was handed over to the Australians for their use Whilst the original Casey station was being built. Since then it has been left unused and has become iced over. Australia has also developed the philosophy of separate individual buildings, whilst the Americans tend to build a single integrated structure. The individual buildings mean greater safety (in case of fire) and also mean that expeditioners must dress and face the outside environment each day, which I believe is infinitely better for our emotional well-being.

Wilkes station has suffered over the years. Its location in a sheltered area has seen most structures buried by the recurring ice (internally as Well as extemally) and is surrounded by tonnes of rubbish. This is another challenge for Australia. We must clean up this area and maintain the heritage-listed old buildings. It is still possible to gain an accurate idea of the living conditions of Wilkes station from the residue at the site – eg boxes of tins of food are everywhere, and when I think that I was hard done by in 1982 (compared to now] then I know that I was in luxury compared with what those guys experienced.

Wilkes Station in January 1996. Photo Brian Brawley

Tuesday. 27th February 1996 — D (for departure) Day. Time to leave Casey and Antarctica for the long rough trip back to Hobart (and Liz, my wife.) The trip back was a bit rougher and a few (lot) of expeditioners felt a bit (very) sea sick. This had its positive side as with 94 expeditioners on board, and only 60 seats in the mess, it made it a lot easier to find a seat.

I had mixed feelings on this leg of the trip. Firstly I was sorry to leave a part of the world that I love, the last frontier that so few people can visit. A place where people of all nations can work, talk, play and experience things in goodwill, and without enmity. Then I envied those people we had left behind who would experience a winter in this remote land, who would have the chance to fulfil their dream of adventure. And lastly, the joy and anticipation of returning home to be reunited with my loved ones. The trip was long and rough; we were hammered quit a bit, but knowing that Hobart was just over the horizon made it worthwhile, and then on Thursday, 7th March at 7am we docked at Hobart wharf. The trip of a lifetime was over. The trip was absolutely, bloody fantastic and to cap it all off Liz came over to Tassie so we spent 10 days making a quick lap of the island. We travelled 2,500 kms and saw a stack of scenic places, but if you think Tasmania is a small, quickly seen place you’re wrong! Next time we plan to spend a month, or six weeks, or…. So two months and one day after leaving Mt Compass I was home again and back to the grindstone. However I have this idea, that if it comes off maybe, just maybe, then there could be another trip back to THE BIG WHITE FREEZER.

In a nutshell, it was a real shock to the system to see the overall size and complexity of the stations, the stores are a real eye—opener. In the ‘good old days’ of ‘82 you got a cake of soap out of the box — now you have a choice of about four different brands!

There is a lot of good scientific work being done, and hard work being completed in the field, but, as in all walks of life, there are some who, I feel, could do more to serve the cause. Some are just using the system for a ‘paid jolly’ and I believe this is regrettable and to the detriment of all expeditioners. But, all in all, the Division, and Australia, should feel proud of the commitment involved in our work in Antarctica.

The work being done in cleaning up and RTA of all rubbish is a real plus. Wilkes needs a big clean-up and both Davis and Mawson need a clean out of the old, run-down buildings – except for two or three of the old huts that should be restored as a reminder of the past. To restore, and maintain all the huts would be just too expensive, and many are just too far gone.

In closing there are a few thank-yous to hand out, to the Division, ANARE and the Director. To Steve Reeves, the Voyage Leader (VL), who was a real pleasure to meet and work with – I take my hat off to him. To Dave Moser, DVL, who is following in Steve’s footsteps, is a real gentleman. To the Captain and crew of the Polar Bird, to a man they were imbued with the best of ‘Antarctic fellowship’, a credit to themselves and their ship’s company. I must admit that I had wet eyes when I shook hands and had to say that final goodbye to the crew. Finally, to the ANARE Club thanks for selecting me. I did all I could to put the aims, and name, of the Club forward, and whilst taking advantage of the extended range of goods and others‘ organisational skills, I believe I broke all records in selling club paraphernalia.