Day 12 Saturday 15 November

Last night, another high latitude experience. At much the same hour (a little before midnight) as two nights ago when I was watching an aurora against a dark sky, I was tonight watching the afterglow of sunset. The sun itself had gone but given the shallow track it takes so far from the equator it was not far below the horizon. The sky was still bright with light and colour, with a pink wash all round, and in the west of line of clouds still burned orange and gold above the departed sun.

In technical terms, we were still in civil twilight, with enough light to undertake everyday activities. I could have read a newspaper, had I had one. Civil twilight ends with the sun six degrees down, and that may have happened soon after the cold drove me indoors. Certainly the fire in the west had gone cold.

But the next stage, nautical twilight, which ends with the sun 12 degrees below the horizon and the horizon itself no longer discernible, would not have ended last night, And without even an entry into astronomical twilight, we would have been denied any view of the stars, even though the sky was clear.

These musings are clearly those of a mid-latitude man, where sunset at eight o’clock (daylight saving excepted) is late enough still to be respectable. Those who live at high latitudes, in upper Scandinavia or Russia or Canada a world used to such “white nights”.

But for the rest of us, a sky is still bright at midnight takes some getting used to. With three degrees still to travel to the Antarctic Circle, and five weeks to pass until the summer solstice, the conjunction of which factors generates the phenomena of the midnight sun, the midnight sky has still some brightening to do.

While I pondered the sky, the pack ice continued to pass. It now covered most of the sea, but being thin, it offered little resistance to the ship. The engines were audible but only just, and we seem to move across a frozen landscape almost in silence.

Perhaps the right word is ” glide”, or perhaps “float” in a metaphorical as well as a literal sense. Only near the ship’s side did the ice take any notice of our passing. It seemed to me we approached Antarctica with as little noise and fuss as James Cook In the Resolution two centuries before. With a pink tinged sky above, and the ice stretching away below, the overpowering emotion was a sense of serenity.

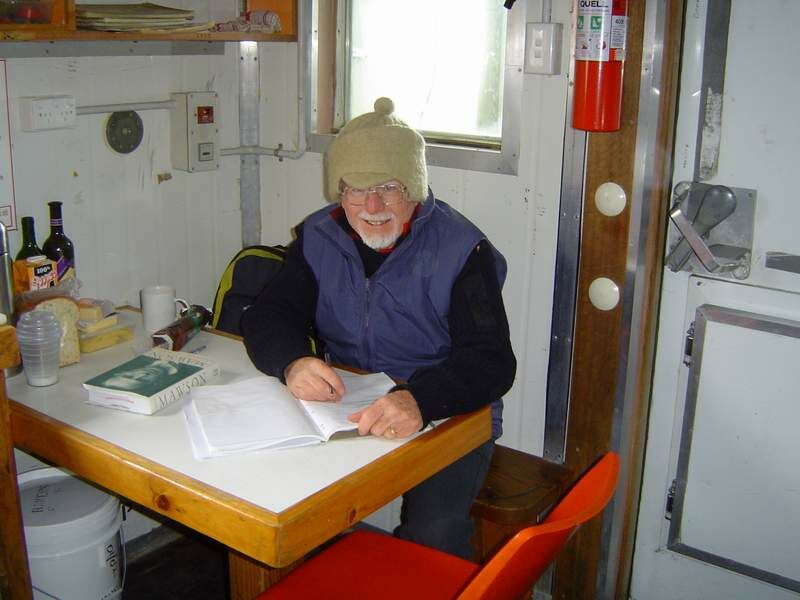

I am in my possie in a corner of the conference room where I spend a lot of my time.

A couple of people have come in to buy post cards, so those stocks are slowly dwindling, and I will do another push before people get off the boat at Davis.

We are pushing steadily through the pack-ice, and the sound of scraping on the hull is almost continuous. I

Cereal for breakfast again today, but by the time I had added some nuts and dried fruit it was as good as you would buy.

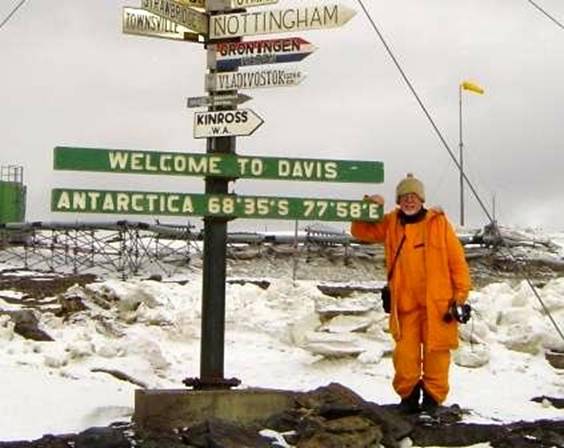

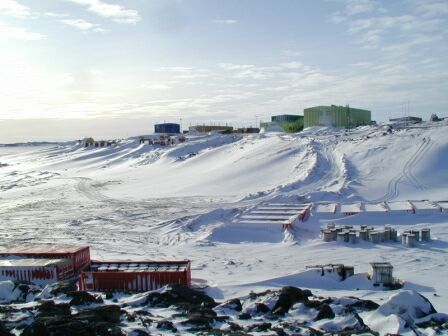

News is that I will not be living ashore once we get to Davis. There is not enough room with over 100 people on the base (including 60 summer trip scientists). The round trippers, the Mawsonites and even some of the Davis people will continue to live on the ship while we are there, though of course we will be going ashore every day.

With a late Sunday arrival and a 23 November departure, will have only six days. They will be busy. On the trip back, the ship will be half empty.

A few things have changed. The sun is shining for only the second day, brightening the sea ice and making dark glasses and sun-cream obligatory. Not a cloudless sky but enough to fire a billion glittering points in the snow covering the sea ice.

Secondly the ice has thickened and often dominates the sea entirely, as far as the eye can see… We are further south and less ice has been melted by the advancing spring. It has not yet an equal contest, but today the ship must work harder to maintain its path. Occasionally, the ice wins, and the ship is brought to a halt. It is forced to back up and to seek another route.

Much of the time, the captain follows a “lead”, a narrow opening in the ice which can wind like a river among the floes. But these leads can close or run out or take the ship in the wrong direction. Then we must cut “across country”, sometimes breaking through, sometimes not.

The tranquility I spoke of earlier is harder to find today. From the bow, and even more from the chamber below the bow where the anchor chains and mooring cables are kept, the noise of battle is unmistakable. The ship is winning, but at some cost in time and effort.

The ice maintains its fascinating variety. Much of the open water, where it occurs, seems smeared with grease. Here layers of very new ice crystals cover the water, dulling its sheen and smoothing out the ripples. A little later, the thickening mats of crystals begin to overlay each other, forming large brighter patches with astonishingly straight sides. I am told this is a consequence of the crystal structure of the ice, the microscopic made large and plain.

To liven the passing ice, we caught our first glimpses of wildlife; a group of a dozen penguins, a few seals and a variety of birds. These, like the currently sparse icebergs, are sure to thicken as we close on the Antarctic coastline.

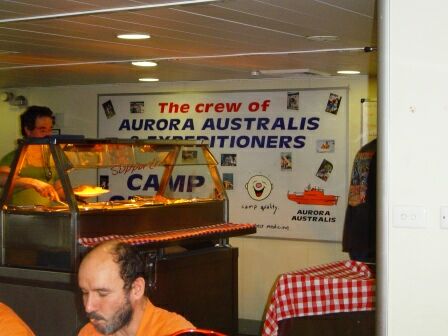

Social activities centered on the Husky Bar last night, with a full house to witness a talent quest under the title “Antarctic Idol”. It was hosted by a couple of the ship’s crew, who succeeded in inducing our Chinese fellow passengers (we are taking them to their base which lies a little west of Davis) to perform. The applause shook the walls. We had some Scottish folk dance music, with dancing (“William Wallace and the Wives”), and a pair of Dusty Springfield impersonators (“The Mawson Girls”), interspersed with jokes from whoever was willing to get up and tell one. A lively and enjoyable night, helped along by infusions of light beer and passable wine. The nights are festivities will be on the trawl deck, where the crew will put on a barbecue.

Watching for the ice slide by from the helideck gave me a chance for a good yarn with Bob Jones, the incoming Station Leader for Davis. He will be the man in the middle for the summer of science, attending to the needs of 100 people, 60 of them scientists. He will stay on to lead a much smaller team through the winter.

At 55, Bob is a veteran of eight voyages south and five winterings, four of them as Leader. When at home in Bendigo, he is a vet. The influences that drew him south for the first time in the 1980s were mixed; reading The Fire on the Snow in school, being in Scouts, getting involved in bird banding (and discovering that some of the birds had come from Sub Antarctic islands).

This lead to trips to Heard Island on expeditions to see why the numbers of elephant seals were declining, and ultimately to winterings at Macquarie Island Mawson and Davis. So Antarctica is in his blood and he keeps going back, though he admits to a certain sense of selfishness.

The hectic pace of scientific research at Davis through the summer is exciting, Bob says. Once the summer parties leave, the winter is a very different experience, with the same sense of isolation as of old despite the improvements in communications. In time, he thinks, the culture of the summer and winter parties will diverge, and the imminent replacement of the long sea voyage by an eight-hour plane trip will accelerate that trend.