REPSTAT REVISITED ANARE VOYAGE 5, 1988/9 – M.V. ICEBIRD

ANARE VOYAGE 5, 1988/9 – M.V. ICEBIRD

By Ian Mackie – Club representative 1998 – 1989

M.V. Icebird departed Hobart on 7 December 1988 with 75 passengers – winterers, summerers, round trippers, supernumeraries and Antarctic Division staff. This was to be the annual resupply and changeover of Casey and would also include the official opening of the “New Casey”.

l was privileged to be on board as the ANARE Club representative, my primary role being to observe and report back to members my experiences, including the Antarctic Division’s current methods and procedures during the resupply of the base.

The trip was particularly memorable for me, having been a member of the Repstat party which constructed the first Casey in 1965/66 under the leadership of Dr. Philip Law. Now 23 years later I was returning to Casey and the Antarctic continent. I hope in this article to express my observations and comparisons of the earlier days with that of the current construction and

change-over methods.

As a supernumerary for the first time, I couldn’t help but be impressed with the scale of today’s operations directed from the Antarctic palatial new headquarters at Kingston. It was avast improvementon the cramped old St. Kilda Road office in Melbourne. For a newcomer it was difficult to find your way round the vast complex, even though all departments were housed

under the same roof. Another opinion expressed by many was that the Division is located too far away from the scene of action at the wharf, resulting in many time-consuming trips to and fro.

Being kitted out with some cold weather gear brought back nostalgic memories of George Smith’s store in the old shed at Port Melbourne. Although the method of distribution has improved, the range of sizes has not. With particular reference to gloves — the only thing missing was George’s booming voice in the back- ground, “you’d better take it mate! tomorrow there’|l be none left!”

I noted that expeditioners are now housed in luxurious accommodation prior to embarkation. “Antarctic Lodge”, a cluster of self-contained units at Sandy Bay, is somewhat different from the unofficial “Antarctic Lodge” in Melbourne (Mrs. Hall’s Guest House in St. Kilda), but l suspect the former may lack the colour and tradition of the latter.

To put us in an Antarctic mood and to strike fear into the hearts of the newcomers, on the morning of departure we were shown a series of films on how many ways you can perish in the Antarctic (by courtesy of Dr. Peter Gormley). We were then quickly bused to the Icebird and participated in lifeboat drill. The only difference these days is that they lower the lifeboats overboard with all expeditioners securely strapped inside, and cruise for 15 minutes around the picturesque Hobart harbour. The view is largely wasted as today‘s lifeboats are fully enclosed. At this point of time, one may have anticipated mass defections from the expedition, but being an intrepid breed, all passengers presented themselves later in the evening for the ship’s departure. At 8 p.m. we were on our way under the leadership of Andrew Jackson (Voyage Leader) and Zena Hyams (Deputy Voyage Leader). Icebird was captained by Ewald Brune.

The trip to Casey could be regarded as calm by Antarctic standards, but Icebird managed to develop a considerable roll even in mildest seas, probably due to the ship being somewhat top heavy and flat- bottomed. Although the more intrepid hoped for rougher seas, the sea sick passengers were not so impressed. All manner of current preventative measure – pills, tapes behind the ears, pressure wrist straps, large quantities of alcohol, or no alcohol, were all tried in various combinationsto ease the pain. Dr. Chris Henderson on board to research motion sickness, longed for heavier rolling, but volunteers for his light flashing, drum spinning experiments were content just to survive.

Accommodation in the passenger module was very comfortable and spacious. I had the company of Anthony (science student) and Arthur (teacher) in my cabin. All other conceivable space was crammed with my ANARE Club saleable items which managed to burst out of the drawers and cupboards at the slighest roll! Life on board was far from dull (more like a Pacific cruise than an expedition) with the girls from Head Office responsible for on-board entertainment, fancy dress parties, trivia nights, cocktail hours and other forms of jollity were the order of the trip. The more adventurous could adjourn to the hold (weather permitting) and practice roping and ice rescue skills with Army Instructor, John Schwetveger, or join in the volley ball tournaments.

The Army boys “Larcies” and “Termites” (cargo handling) under the leadership of Lt. Ray Jones did a marvellous job during change over, and as usual upheld the fine Army traditions aboard lcebird.

I did my utmost to promote the ANARE Club, and although I signed up some new members I found that many people had misapprehensions as to the aims and joining requirements of the Club. Suggestions noted as to how the Club can improve its presentation and recruitment are currently being considered by Club Council.

Wednesday 14th: “King Neptune” appeared on deck and dealt out his dreadful indignities to all who did not possess the appropriate credentials. With the taste of a vile concoction and iced water down the neck, all adjourned to the stern for a “pack- ice” barbeque.

The arrival at Casey that evening was marked by the blasting of Icebird’s horn, and the responding flares from the base. Still a bit tame when compared with explosive arrivals of years gone by! Anchor was dropped at 6.30 p.m. and a barge lowered along side. Urgent stores, mail and key personnel went ashore that first night. I was beginning to get itchy feet wondering what it would be like to set foot again on Repstat/Casey after 23 years. For that night at least I had to content myself with the view of the old station with the new station dominating the skyline, its huge buildings catching the reflection of the setting sun. Sadly, not far away the remnants of the old Wilkes could be clearly seen with its twisted and bent radio masts still standing defiantly and the old yellow radar dome bright in the evening sun. High on the hill stood the crosses of two expeditioners tragically killed in early expeditions – a sober reminder of what

can happen in this unforgiving land.

The banana belt weather continued with a brilliant sunny day. As I took my first step from the landing barge I was greeted by the familiar smiling face of Doug Twigg who was at Casey for the summer. The short walk from the wharf to the station through the slush empasised the value of the old DUKWs and later LARCs where you were deposited right outside the station

mess room!

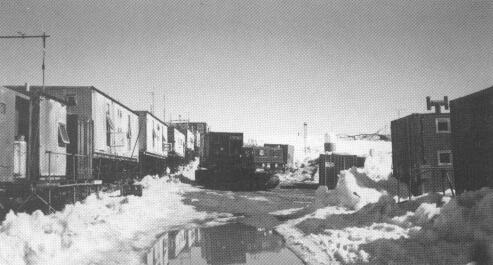

My first impression was that they had at last completed the magnificent new station we left half erected in February 1966, with all the missing buildings filled in the line, and with the inter-connecting famous tunnel. My second impression was that our then famous new (“old”) station now looked ready to fall down with rust and gaping holes in most of the panels, and

other obvious signs of wear and tear. The intervening 23 years of harsh Antarctic weather had taken its toll. Although at the time the design features were revolutionary and sound, it was clear that the materials used left much room for improvement. However, it must be remembered that in those days there were severe funding problems, with Davis being shut down for

five years to re-allocate funds and resources to build Repstat over a similar period. The same financial restraints do not appear to exist today.

Ian Mackie and Doug Twigg at Casey

Old Casey Station (Photo by I. Mackie)

A briefing in the Mess to all newcomers by O.I.C. Tom Maggs explained the safety rules and station procedures, and a welcome hot cuppa and heaps of cakes reminded me of the great cooking feats of “Mumbles” Walker in the Repstat days. All round trippers went about their allocated tasks assisting with the unloading of stores and the moving of equipment to the new

station up the hill. I very quickly slipped back into the Antarctic routine again as “first day slushy” – some things never change! Chris, the cook, did a fine job in the old kitchen catering for over 100 hungry personnel. The atmosphere in the Mess was crowded but comfortable, and I noted the inside of the old buildings had stood up much better than the outside to the years of wear.

By far the biggest attraction for me was to finally after all these years walk up the legendary 1000 feet long Casey tunnel, only partially completed in 1966. lt seemed a very practical concept with all various buildings inter-connected with this corrugated iron structure. As we progressed up the tunnel, new departments appeared on our right rather like a shopping arcade – radio – Met – Glaciology etc. I was mystified by a room marked “Noeleens” with a bright electric sign, but a quick glance inside revealed what my nose already suspected, this was the “latrines”. After a seemingly unending walk we arrived at the end of the tunnel and out into the Antarctic sunshine. Here before my eyes stood the old power house and vehicle workshop, still in service, but the outside looking the worst for wear. A close inspection revealed several unsuccessful demolition jobs by vehicles colliding with the building. The inside appeared sound and serviceable and the Repstat boys would be proud that this steel framed type building they erected looked good for a few more years to come. Although I heard the concrete floor was replaced some years back.

About one-third of a mile up the steeply snow banked road stood the new station. Before we could reach it, however, we had to run the gauntlet with the busy change-over vehicular traffic. Three wheel and four wheel “all terrain motor vehicles” zipped up the road amongst the slower trucks and huge tractors hauling trailers and containers – certainly not a place for pedestrians. The only escape was up the bank.The first building to impress the visitor is the green store shed on the right standing about 60 ft high, huge by Antarctic standards. It had a

fully palletised storage system moved around by concertina type shelving on rails, towering up into the rafters. Electric fork lifts moved the pallets around. The building also housed a freezer and a warm stove. I was to get to know this building much better in the next few days as a budding apprentice storeman. The task – to unload and stack countless tins of biscuits and crates of eggs and other goodies. Judging by what we unpacked the ‘89 winterers should dine like royalty.

Apart from the smaller but equally important modular type buildings at the new station, the edifice that strikes the visitor most is the huge “Red Shed”, the living and domestic quarters. The first impression on stepping through the eighteen inch thick doors is, “Can this be Antarctica”. It is certainly more like a foyer of a five star hotel with its striking marble stair-case, carpeted floors, inside balcony and tasteful light fittings. The concept is very open and spacious, and there are magnificent million dollar views out of the floor-to-ceiling windows visible from the bar area and the spacious cafeteria style eating area. Moving into the living area (another name for“dongas”) one proceeds down carpeted corridors with the individual bedrooms leading off. each man’s room was tastefully fitted out with a normal bed (no more climbing up the bunk ladder after a wild ding) and dressing table. While not over large, I felt the rooms were about

twice the size of the old dongas. I heard that each room has provision for its own telephone; toilet and bathroom facilities equal to any hotel standard also lead off the corridors (all flush toilets naturally).

Ample recreation rooms — films, library, music etc. are included in the complex. However, one suspects that an expeditioner may be tempted to spend the year in his bedroom, complete with his personal computer and video. Have we seen the end of the traditional “donga party”?

I was assured by the Housing and Construction boys that these new buildings have an indefinite life providing the outside panels (easily removed) are changed every 20 years or so. Technical details of the construction methods used will appear elsewhere in this or future editions of your Aurora.

All the buildings are serviced with electricity, hot/cold water, phone, fire sprinkler systems. All these services are carried round the station on service trays easily accessible for maintenance using the “ring man” system.

All day trippers assembled at the wharf at 5.30 p.m. for the rather chilly 20 minute trip back to Icebird aboard ANARE barge “Fred Bond“. The usual scramble up the ship’s ladder and roping up of bags etc, was to become a part of our daily routine over the next few days. A regular guest was a Leopard seal which circled the ship during the entire change-over waiting for a juicy expeditioner to fall into the water.

Over the next few days changeover ran very smoothly with the cargo being shipped to shore on the barges, then lifted onto the trucks and trailers by the huge 40 tonne crane brought down on lcebird. At the appropriate location the containers were off loaded by all-terrain forklifts — a very neat operation that required very little man handling of goods. It became obvious that the round tripper played no role in this sophisticated operation and would only be in the way. How different from the last time I was down south when every spare body

was involved with unloading from dusk to dawn. However, we were able to offer valuable assistance in other areas of the station relocation and movement and racking of stores. I observed that as usual the old winterers regarded with suspicion supernumeraries of any type, and particularly Head Office personnel. One had to be extra careful not to offend traditions that had built up over a year. I also detected that dyed-in-the-wool tunnel winterers, with a feeling of great affection for the old station, wanted little to do with the cold untraditional new edifice up on the hill. Feelings ran so high it was obvious old winterers staying on for the summer would not budge even if it meant a diet of baked beans on toast in the vastly depleted old station. An effective compromise was reached: incoming station leader, Joe Schmiechen, placed the old station under the charge of the legendary Doug Twigg (OIC Casey 78). Doug moved

into the old OIC‘s quarters in the tunnel when current OIC, Tom Maggs, departed on Icebird, and Joe moved into the new palatial OIC’s quarters in the “Red Shed”. Those wishing to remain in the old station could stay with minimal cooking and eating facilities, breakfast only (do it yourself) with all main meals being served in the new station.The intention was that at the end of summer the old station would be closed down and eventually removed with the exception of a few of the top huts which would remain as work areas for the next few years. Apparently this met with the approval of the tunnel dwellers and all was well again. To emphasise the point, some anonymous expeditioner hopped in the dozer late one night and blocked off the road to the new station with snow. This was easily removed the next morning, but the point had been made.

Saturday 17 December was indeed a notable day. First of all it was the last official meal in the old station, and nearly 100 personnel crowded in for a memorable buffet tea. The next day all meals were to be cooked in the new station. OIC Tom Maggs mentioned the significance of the occasion and how the station moved from Wilkes in 1969, and now onto New Casey in

1989. It was also significant for me, having been involved in the construction of this Mess Room, and now having the last meal in it. I was also present for the first meal in January 1966 with Geoff Smith and his Repstat.

I stayed on shore that night and set up shop in the Mess where I sold items for the Club and signed up some new members. Interest was fair only, but Tom Maggs had done a great job promoting the Club during the year and most were already members. A few beers in the “Casey Club”, which was originally our old dormitory in the construction days, brought back

happy memories. After a rather late night with the hard working Army lads I scored a vacant donga and settled in to a claustrophobic but cosy night as a genuine tunnel dweller.

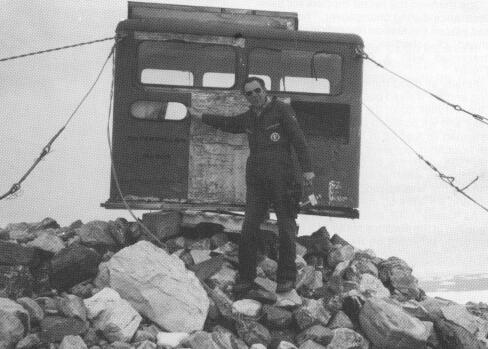

Sunday 18 December I was rostered to visit Wilkes. The good weather was holding, and along with other intrepid round trippers we crowded into the back of a Hagglund (a tracked over snow vehicle) and packed ourselves in with rubber mats, sleeping bags, and anything else that would stop us rattling around. This must have been one of the roughest trips I have ever experienced as the vehicle bounced over the sastrugi. But it was all worthwhile and to my surprise when we alighted we were not yet at Wilkes but had taken a diversion to that famous Antarctic tourist attraction “Jacks Donga” — an old tractor cabin perched on a rock. It was exactly as I remembered it from 1966, if anything, more precariously placed. We again

boarded and bumped our way over to Wilkes, where we were free to wander around the ice buried station for the afternoon. This was a great opportunity to take photographs and experience first hand a station which was the source of so many experiences for our old 1966 Repstat Construction crew. In those days a weekly trip from Repstat to Wilkes for a shower,

shave, to do some laundry and take in a movie was a luxury.

To see the station buried to the roof was sad , but inevitable as it was only built as a temporary base by the Americans in 1957, but subsequently inhabited by the Australians from 1959 to 69. To me some cleaning up seemed in order, but it was no way near as bad as others have made out as an environmental hazard.

Finally the big day, the 20th December arrived, the official opening of the new station. Prior to this we all gathered for the last official ceremony in the old Mess – a memorable occasion, when Tom Maggs handed out Antarctic medals and photographs to his wintering party. We then adjourned to the new Red Shed for the opening by radio telephone by Senator G.

Richardson. When the keys of the new station were handed over to Joe Schmiechen by Tom Maggs, Doug Twigg and Graham Manning were also on the “stage”, making four Casey OIC’s present at the ceremony. Capt Ewald Brune presented the station with a model of Icebird inside a bottle, and a case of Icebird champagne.

Joe thanked the round trippers for their assistance during changeover. “Your help had placed the station relocation plan well ahead of schedule” he said. All were presented with a Casey 89 souvenir T-shirt.

Finally all good things must come to an end and we walked back to the old station. One last walk down the tunnel for old times sake and we boarded the Army barge and

returned to lcebird in the harbour. About an hour later, we were joined by Tom and his 1988 winterers, by now all in fine form. Still the fair weather held, and at 5.30 p.m. the anchor was raised, engines burst into life and we were on our way home. As Casey (old and new) and Wilkes receded in the distance many, still gathered on deck, reflected on their stay at Casey, be it a summer, winter or round trip.

Ian Mackie and Hagglunds.